If you’re anything like me, you probably hated that title. Hell, I hated typing it! But this is a post about ersatz, and as algorithms are some of its main purveyors, it seemed fitting to start with some clickbait.

The last time we met in this space, I talked about the growing thirst for authenticity I perceive in the overculture. Whether that perception is accurate remains to be seen, but ultimately it doesn’t really matter. Houston, we have a problem either way.

If you haven’t already read that post, I recommend that you do so before continuing. Then, my focus was on the science of perception, processing, and bias. Or to quickly summarize: No human perceives reality as it actually is. Instead, we navigate this existence via a working model created and constantly modified by the brain in response to sensory input. This was what I meant by the “unrealness” of reality—a term of my own creation. As someone for whom words are containers for meaning, I often find myself crafting containers for the families of meaning that don’t fit my mother tongue’s current forms.

Simply put, my “unrealness” container is a stand-in for “perception” that also implicitly acknowledges that we humans all experience reality by proxy. If we let it, it can serve as a reminder that the “real” is often not nearly as important as the stories we tell to give it shape.

In my previous post, I mostly stuck to the most common scientific “maps” of this particular territory. However, as the saying goes, “the map is not the territory.” And in my opinion, those scientific maps are missing some layers. They show the equivalent of roads, landmarks, and businesses, but say nothing of the topography, ecosystems, and local culture of a place.

Here begins the process of filling in some of the missing layers that are not so easily labeled or explained. The souls-filled and magical. The inspired and Unseen.

Well, would you know yet more?

Ersatz Like Cobwebs

First though, a story of a dream (so really, a story within a story).

How delightfully meta!

The year was 2022, and my family and I were visiting my parents back in Lancashire, England during the winter break. It was my first trip back in over a decade, and my daughter’s first trip to where her mother grew up.

One night while there, I had a dream. I was rushing along country lanes, long and winding like snakes, the land around me smothered by layers of cobwebs. Now, these weren’t some Otherworldly roads, mind you. That’s just how a lot of the lanes there are—winding serpents of pitch and gravel through tunnels of trees. All snakes I’d set my boots to countless times in waking life.

After a while, I came to a stop and turned to the hedgerow lining the lane. Somehow, I knew I’d reached my destination for the night—that that was where I was supposed to enter. By this point, I was fully lucid in my dreaming. I could have easily turned back the way I came. But Necessity was loud in my souls, so I pushed through the shadows and thorns until the hedge opened up, and I found myself in what appeared to be a council chamber.

Looking around, I saw that numerous peoples had gathered there for a meeting—everybeing from the plant, tree, and animal peoples to the Unseen and Otherworldly. As the only human there, it wasn’t long before I attracted some attention, though perhaps not in the way you might think. Apparently, we humans had always had a place at the meeting. It had just been a good long while since any of our kind had last filled those seats.

The reason, I was told, was the cobwebs. According to my hosts, what I’d perceived as webs were really the layers of stories woven over the human population by those who’d remain in control. The only reason that I finally made the meeting (or could even see those webs to begin with) was because my time away had first loosened, then shaken their hold. Nowadays, I wholly believe those “webs” are what people are referring to when they speak of “the veil.”

Toward A Definition of Ersatz

No matter its name, that barrier or binding is largely what I mean by “ersatz.” My container this time is obviously a borrowing altered from its original form. But “container” struggles seem par for the course when it comes to discussing this subject. The writer James Joyce, for example, named his container “false art” or “improper art,” which J.F. Martel summarizes in the following way:

’Proper art stills us, evoking an emotional state in which “the mind is arrested and raised above desiring and loathing.” Improper art does the opposite, aiming to make the percipient act, think, or feel in a certain prescribed manner.’ (Martel, Reclaiming Art In The Age of Artifice. 26-27).

You may wish to put a pin in that part about “desiring and loathing.” I’ll be returning to it toward the end.

Much like that “false” or “improper” art, my borrowed “ersatz” is any story that binds and keeps us closed off to inspiration, and/or controls and makes us another’s tool or weapon. Ersatz is the stories that trick us into believing ourselves separate from, maybe even better than, other humans due to inborn qualities. It’s the stories that have us reaching into our pockets for money we don’t have for some product to fix everything (usually while also convincing us that we’re brands too).

Tired of Capitalism 1.0? Try Capitalism 2.0 instead! Think you know REAL Capitalism? Think again! 100% guaranteed to make you rich!

(Terms and conditions most definitely apply.)

Ersatz is propaganda and marketing and nationalist myths of blood, soil, and divine destiny. It’s the various “programs” or ideologies by which our societies run. To quote Martel again (who’s clearly also in the container business), ”Proper art moves us, while artifice tries to make us move.”

And unfortunately, that artifice or ersatz is more prevalent than ever before.

According to Samuel Spitale in the introduction of How To Win The War On Truth, the average American is subjected to anywhere between 4,000 to 10,000 media messages a day (up from around 1,600 fifty years ago).

No wonder so many of us struggle to find the space for Authenticity’s seeds.

Weaponized Ersatz: A Two-Headed Beast

So, we have our ersatz, already monstrous but still growing. Worse still, this beast is polycephalus. For the purposes of this post, I’ve set a two-head limit for this word-woven creature. After all, nuance often gives way to endless rabbit holes without proper boundaries. And well…this post is already a warren.

With that said, let’s meet our fiend!

A loud roar suddenly shatters the silence as the beast rises. Its feet make dust of hard rock. Terrified, you begin to retreat, your heartbeat a war drum in your chest. The land shakes as it takes a step, and, unable to look away, you stumble and lose your footing. Palms aching, you take to shuffling backward on your butt—anything to escape. But then the land shakes again as it takes another step, and realization sinks in as hard as the stone making raw meat of your skin. Your desperate shuffle could never match a monster’s stride. Blood like ice, you freeze. Instead, you stare at the two heads swaying like snakes, their mighty maws open wide, and prepare for the end.

Dear Gods, please let it be quick…

One head lowers, and you find yourself choking on its breath. “WHEN YOU’RE HERE, YOU’RE FAMILY!!” it bellows, the words so loud they rattle your bones.

A half-second later, its twin lets out a second booming slogan. “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!”

The laughter slips out before you realize it.

“Fuck me, Marketing and Propaganda?” you manage between cackles. You sound insane, and maybe you are, but this beast makes crazy people of us all anyway. The two heads cock to one side, and you laugh even louder. “I’d rather a fucking demogorgon!” you snort.

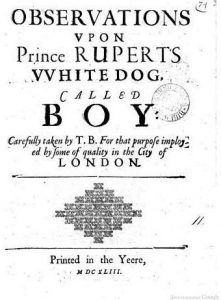

![]()

(Me too, fictional scenario person. Me too. At least demogorgons aren’t the bestial equivalent of glitter.)

A Natural History Of Glitter

When I first began looking into the history of this beast, I’d assumed it would be easy. There are, after all, entire courses on these subjects. However, I quickly found that most of the relevant sources treated marketing and propaganda as completely different entities rather than parts of the same beast.

In my opinion, this is a flaw at best. Not only does it obscure the commonalities between the two heads, it also shrouds the extent of its reach in our lives. Worse still, I would argue that, much like Pavlov’s salivating dogs, the marketing we consume as benign actually primes us for propaganda as well.

But more on that shortly.

Whenever I research a subject, I first seek out the root—the “origin story,” so to speak. Without those “first layers” or “prologue,” I find it hard to fully anchor a subject in my mind.

Unfortunately for me, this glittery beast has no clear parentage. That tendency to see two different beasts instead of a singular fiend obscures its origin story as well. So, a person working within the “two-beast” model with a focus on marketing, for example, might cite Adam Smith as the father, as he is considered the originator of the concept. However, a second person with a focus on propaganda might cite Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays, as the father of “public relations” (itself a rebranding of propaganda) instead.

Faulty modeling aside, however, we are dealing with the same beast. In his 1928 book Propaganda, Bernays writes about propaganda and public relations for commercial and political ends without differentiation. Where nowadays we might say that marketing sells products and propaganda ideas, it was all the same toolkit to Bernays.

Interestingly, he also makes it clear that a group he refers to as the invisible government—shadowy figures who understand the mechanism and motivations of the public mind—uses that same toolkit to rule over the people as well (Bernays. 9-10).

”The minority has discovered a powerful help in influencing majorities.” (Bernays. 19).

Given that the “powerful help” is our beast, it’s little wonder the mist between the two heads is so damn thick!

The last time I darkened this digital domain, I talked about some of the recent research into perception, emotion, and bias. Now obviously, Bernays had none of those modern discoveries to pull on, but he was very familiar with his uncle’s work (as well as that of some of his contemporaries). Where his predecessors, the “old propagandists,” relied on “the psychological method of approach” (in other words, arguments based on facts and logic), Bernays focused on influencing the “mental pictures” in the public mind (Bernays, 106-107).

”Modern propaganda is a consistent, enduring policy of creating or shaping events to influence the relationship of the public to a given enterprise.

This practice of creating circumstances and of creating pictures in the minds of millions of persons is very common. Virtually no important undertaking is now carried on without it, whether that enterprise be building a cathedral, endowing a university, marketing a moving picture, floating a large bond issue, or electing a president.” (Bernays, 25)

Over the years, Bernays worked on both commercial and political campaigns alike, influencing American life in surprising ways. In the 1920s, for example, a time when smoking was not so common among women, Bernays ran a campaign for Lucky Strike that equated smoking with women’s rights and presented cigarettes as “torches of freedom” (Spitale. 14-16). It’s also thanks to Bernays that hairnets became ubiquitous in food service. As shorter styles became more fashionable among women, hairnet sales sank. To remedy this, Bernays convinced health officials to make them a requirement for food service workers (Ibid. 16). He is also why people came to consider disposable cups cleaner than reusable options, and why men now also wear wristwatches and no longer consider them women’s jewelry (Ibid.)

Most infamously, however, Bernays produced propaganda for the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) against the democratically elected government of Guatemala, labeling them “communists.” This helped to enable a CIA-backed coup that led to decades of dictatorship and civil war for the poor people of Guatemala (Ibid. 16).

(This was also the origin of the term “banana republic,” by the way.)

So yeah…absolutely abhorrent.

As significant a parent as Bernays was though, he’s clearly not the only “daddy” in the mix for our beast. Unsurprisingly, this being is more homunculus than anybeing naturally spawned. (Gods, what a collection of words!) Moreover, there may also be some earlier, magical parentage as well.

Marketing, Propaganda, And The Magic Of Desire

This next part begins with the work of Ioan Petru Culianu. In life, Culianu was a Romanian-American historian known for his books on certain niche aspects of renaissance thought. A practicing magician who sadly met his end in 1991 in his bathroom courtesy of a bullet to the head.

A murder that remains unsolved to this day.

Well anyway, one of Culianu’s main academic foci was the writings of Giordano Bruno, a friar-turned-magician who was burned for heresy in the year 1600.

In his book Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, Culianu uses Bruno’s essay On Bindings In General as a framework to examine the possible connections between renaissance magic and mass-media marketing. For Bruno, the key to magic was eros (desire). Along similar lines, modern advertising manipulates consciousness via images that spark desire. Sex sells either way.

Nowadays, we don’t typically think of marketing and propaganda as magical arts. However, Culianu considered this desire-based manipulation the very foundation of political power in modern industrial nations (referred to by Culianu as “magician states”) (Greer. The King In Orange. 19-21).

A Souls-Familiar Layer?

Emotions have long been understood to be magically potent. In Heathenry, the furious god is also the “Father of Galdr” or verbal charm magic. A form of magic that not only marries narrative (and sometimes also poetic meter) with intense emotion and modes of performance. Speak a galdor while utterly enraged, and you’ll probably get some spectacular (not to mention quick) results.

However, fury isn’t the only emotion that appears in connection with magic in the Norse sources. The other main emotion was familiar to both Bruno and Bernays.

Desire.

In the Old Norse sources, both fury and desire are stirrings of the same soul. This is the Hugr, the most “occult” of a person’s souls, you might say. Although better attested in Norse sources, cognate forms appear in all the older Germanic tongues, all of which rooted other words. Among the early English, Hugr was known as Hyge, while a speaker of Old Saxon would have referred to their Hugi instead. In Old High German, the word was Hugu, and in Gothic, it was Hugs.

Broadly speaking, Hugr is “mind,” “heart,” “desire,” and “longing,” though I should also note that these cognates do differ slightly in meaning. For example, the Old English Hyge could be “thought,” “mind,” “courage,” “intention,” “heart,” “disposition,” and “pride.” The Gothic Hugs, however, primarily carried meanings of “thought,” “intelligence” and “understanding” with none of the heart.

Overall, the best summary of Hugr as I understand and experience this soul comes from Snorri Sturluson in Skáldskaparmál chapter 86:

“Thought (Hugr) is called mind and tenderness, love, affection, desire, pleasure…Thought is also called disposition, attitude, energy, fortitude, liking, memory, wit, temper, character, troth. A thought can also be called anger, enmity, hostility, ferocity, evil, grief, sorrow, bad temper, wrath, duplicity, insincerity, inconstancy, frivolity, brashness, impulsiveness, impetuousness. (Faulkes trans. 154.)

As I said earlier, they are the most “occult” of our souls. At times in the sources, they give counsel, while at other times they appear to be a ward. A protector. They are also a wanderer, capable of independent movement from the human whole.

Most important of all though, Hugr has force. They are the fury in the galdor and the lust in the seiðr, they are the difference between empty words and gestures, and tangible result. Hugr is what makes Wish real in the world.

All of which makes Hugr the main prey of our two-headed beast.

Where marketing works to ensnare Hugr with bait made of carefully crafted wishes, propaganda ensnares by stirring up rage and offering nightmarish possible futures to appeal to Hugr-as-ward. If we’re not careful, this beast can make monsters of our Hugr over time as well.

And that, Hel-friends, is a recipe for disaster that lasts long after the screen has gone dead.

Final Words

I was planning to follow up with another post on this topic directly after this. However, the thing about exploring such huge subjects is that, sooner or later, I begin to feel trapped. Suddenly, I find all kinds of other things to talk (ahem, rant) about and find myself getting annoyed. Eventually, I lose interest and cease writing full stop.

So, this time I’m trying something different.

I’m going to post that stuff anyway instead of trying to stick to one series at a time. Expect the unexpected, I guess!

That said, I’m not nearly done with this subject. So far I’ve focused on the effects on individual humans, but I’m yet to touch on mass effects. What happens when significant numbers of Hugr-twisted humans obsess over a practitioner of New Thought who markets themself as a brand? How about when big tech takes a huge dump in the information space? More importantly, why even take that dump in the first place after warning of its dangers less than a decade ago?

The technology might well be new, but the playbook really is not.

Until that next time though, I really encourage you to check out Winifred Rose’s work on Hugr. One of the very best things I’ve ever done for myself both as a human and Wicce is to get to know mine. Nowadays, my Hugr and I are more intentional in our collaboration. Better still, we’re both learning to spot that beast’s bait.

An important practice in our increasingly brain-cooked world full of people with out-of-control and twisted Hugr-souls!

So, until then, be well, Hel-friends and stay safe.

<3

Sources

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda (Original Classic 1928 Edition): The Definitive and Complete Masterwork on Public Relations. 2025.

Greer, John M. The King in Orange: The Magical and Occult Roots of Political Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Martel, J.F. Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2015.

Spitale, Samuel C. How To Win The War On Truth. 2022.

Sturluson, Snorri. Edda: Prologue and Gylfaginning. Translated by Anthony Faulkes. Oxford: Oxford University Press (UK), 1982.

de France. In one of her lais, Bisclavret, a man-turned-werewolf is prevented from returning to his shape of birth by an unfaithful lover hiding his clothes. You see, when it comes to masking and its sibling, shapeshifting,

de France. In one of her lais, Bisclavret, a man-turned-werewolf is prevented from returning to his shape of birth by an unfaithful lover hiding his clothes. You see, when it comes to masking and its sibling, shapeshifting,  ”Woden worhte weos, wuldor alwalda,

”Woden worhte weos, wuldor alwalda, the island of Sámsey. There they encounter a ‘tree-man’ who speaks to them of his purpose and origin. He was the product of sacrifice, and had been made to bring about the deaths of men in the southern part of Sámsey. But over the years, he’d become overgrown and his clothes and flesh rotted away.

the island of Sámsey. There they encounter a ‘tree-man’ who speaks to them of his purpose and origin. He was the product of sacrifice, and had been made to bring about the deaths of men in the southern part of Sámsey. But over the years, he’d become overgrown and his clothes and flesh rotted away. makes the sacrifices until he receives a favorable oracle when he has a piece of driftwood brought in and fashioned into the shape of a wooden man. Then with “the monstrous witchcraft and python’s breath” of those two sisters, as well as the heart of a man sacrificed for the purpose and the proper attire for a man, they sent their tree-man, now named Þorgarðr, into the world to kill Þorleif (North 93 – 95).

makes the sacrifices until he receives a favorable oracle when he has a piece of driftwood brought in and fashioned into the shape of a wooden man. Then with “the monstrous witchcraft and python’s breath” of those two sisters, as well as the heart of a man sacrificed for the purpose and the proper attire for a man, they sent their tree-man, now named Þorgarðr, into the world to kill Þorleif (North 93 – 95).

them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them.

them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them. with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>).

with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>). ‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts.

‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts. in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them.

in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them. before, it can be one hell of a wake-up call to realize what others can do to you, your loved ones, and your life with magic. And for those of us who’ve been through the mill a few times, it can be triggering because you remember how fucking awful it was all those other times.

before, it can be one hell of a wake-up call to realize what others can do to you, your loved ones, and your life with magic. And for those of us who’ve been through the mill a few times, it can be triggering because you remember how fucking awful it was all those other times. lot of them like that feeling of helplessness, sapped energy, and decline in mental (and physical health) can all affect your ability to respond. Depending on what has been done to you, you may not even be able to do anything at all!

lot of them like that feeling of helplessness, sapped energy, and decline in mental (and physical health) can all affect your ability to respond. Depending on what has been done to you, you may not even be able to do anything at all! drain you.

drain you. work has created. However, on another, it’s still giving them access to your mind.

work has created. However, on another, it’s still giving them access to your mind.

magical attack. Because if you place too much belief in the possibility of being cursed or attacked, then it’s all too easy to see malefic magic and psychic attack at every turn and become paranoid. There’s also a lot to be said for self-fulfilling prophecy here – especially with the more magically-minded. But if you refuse to even consider the possibility, then you run the risk of missing some of the earlier warnings and allowing things to become far worse.

magical attack. Because if you place too much belief in the possibility of being cursed or attacked, then it’s all too easy to see malefic magic and psychic attack at every turn and become paranoid. There’s also a lot to be said for self-fulfilling prophecy here – especially with the more magically-minded. But if you refuse to even consider the possibility, then you run the risk of missing some of the earlier warnings and allowing things to become far worse. This is where it gets pretty tricky, and also why you shouldn’t just rely on one thing when assessing whether or not you’ve been cursed. However, a good starting question to ask yourself is if what is happening is logical given the surrounding causes and conditions. For example, if you happen to lose your job and your house is foreclosed on during a time of economic downturn, it’s easy to see the circumstances at the root of your situation.

This is where it gets pretty tricky, and also why you shouldn’t just rely on one thing when assessing whether or not you’ve been cursed. However, a good starting question to ask yourself is if what is happening is logical given the surrounding causes and conditions. For example, if you happen to lose your job and your house is foreclosed on during a time of economic downturn, it’s easy to see the circumstances at the root of your situation. by accident from others, or the result of a curse directed at you.

by accident from others, or the result of a curse directed at you. dying off, then there’s a chance that someone is working against you. This is especially the case when this happens in conjunction with any of the other factors mentioned here. Some folks also keep an egg on their altar as a kind of hex alarm and watch for it breaking. Of course, you may go through quite a few eggs, and will need to remember to change them out if you opt to do this.

dying off, then there’s a chance that someone is working against you. This is especially the case when this happens in conjunction with any of the other factors mentioned here. Some folks also keep an egg on their altar as a kind of hex alarm and watch for it breaking. Of course, you may go through quite a few eggs, and will need to remember to change them out if you opt to do this. often forgotten. And I get it, it’s easy to lose your head when you suspect that magic is being thrown around – especially if you’re already a little battle-scarred before figuring out what’s going on. However, if someone is working against you and you give into that fear, you help them in their cause.

often forgotten. And I get it, it’s easy to lose your head when you suspect that magic is being thrown around – especially if you’re already a little battle-scarred before figuring out what’s going on. However, if someone is working against you and you give into that fear, you help them in their cause.

middle of them, and although I haven’t really found good scholarship on them, my experience has been that these are both effective tools and apotropaics. They’re protective against the Unseen, and allow you – again, in my experience – to see through glamours and things that are normally unseen if you look through them.

middle of them, and although I haven’t really found good scholarship on them, my experience has been that these are both effective tools and apotropaics. They’re protective against the Unseen, and allow you – again, in my experience – to see through glamours and things that are normally unseen if you look through them. general because it has so many uses. You can use it to salt boundaries, protect, and banish. But black salt is just taking regular old salt and leveling it the fuck up! The addition of iron, ash, and (in my case) ground wolf bone, makes black salt an excellent addition to a go-bag. It’s like an apotropaic powerhouse!

general because it has so many uses. You can use it to salt boundaries, protect, and banish. But black salt is just taking regular old salt and leveling it the fuck up! The addition of iron, ash, and (in my case) ground wolf bone, makes black salt an excellent addition to a go-bag. It’s like an apotropaic powerhouse! energy that might “grow up” to get its own ideas and start its own trouble. Spun fiber can provide a bridge, delineate space, and serve as an offering in its own right. I have two spindles that I typically use in ritual work: one is a collapsible spindle that fits in my bag; and the other,

energy that might “grow up” to get its own ideas and start its own trouble. Spun fiber can provide a bridge, delineate space, and serve as an offering in its own right. I have two spindles that I typically use in ritual work: one is a collapsible spindle that fits in my bag; and the other,  my large one, was a gift to thank me for help given. I adore my large one because it feels weighty and authoritative – like a wand. It’s something I’ve wielded in ritual before now when opening portals and working my will. The collapsible one lives in my purse (yes, it’s that small) along with the sheep knuckle I use for yes/no divination.

my large one, was a gift to thank me for help given. I adore my large one because it feels weighty and authoritative – like a wand. It’s something I’ve wielded in ritual before now when opening portals and working my will. The collapsible one lives in my purse (yes, it’s that small) along with the sheep knuckle I use for yes/no divination. resonance to this item that just works. I’ve engraved it with words of power (which I won’t show here), and it’s one of my favorite spirit weapons for subduing, setting up some hardcore protective space, or for when things go bad. I don’t know whether it’s wholly iron or steel (which is mostly iron anyway), but it’s kickass anyway.

resonance to this item that just works. I’ve engraved it with words of power (which I won’t show here), and it’s one of my favorite spirit weapons for subduing, setting up some hardcore protective space, or for when things go bad. I don’t know whether it’s wholly iron or steel (which is mostly iron anyway), but it’s kickass anyway. This is one of my more McGyver-type items. Red thread can be used to bind and protect, or create new items (like a crossroads effigy or protective rowan cross). It can also be used for knot spells, marking off space, and much more. The yarn I use is hand spun with intent and then ritually consecrated.

This is one of my more McGyver-type items. Red thread can be used to bind and protect, or create new items (like a crossroads effigy or protective rowan cross). It can also be used for knot spells, marking off space, and much more. The yarn I use is hand spun with intent and then ritually consecrated.

Having said that though,

Having said that though,  of the matter is that magical practitioners have been finding helping spirits and making pacts with them for a very, very long time. And like wands, familiars traverse a wide range of different cultures (albeit under different names – obviously).

of the matter is that magical practitioners have been finding helping spirits and making pacts with them for a very, very long time. And like wands, familiars traverse a wide range of different cultures (albeit under different names – obviously). Wilby’s period of study. Hall traces a pattern of witches working with mound-connected elves from the tenth century Old English magico-medical charm Wið Færstice and term ælfs?den (literally “elf-Seiðr”, or “elf-magic”); to Martin Luther’s account of being “shot” by a neighborhood witch; and finally to Isobel Gowdie’s accounts of encountering the Queen of Elfhame in a mound and seeing elves fashioning the shot. I personally take it somewhat further and point to the portrayal of Frey and Freyja in the Ynglingasaga. Freyja as the sacrificial priestess (and as we know, goddess associated with the form of magic known as “Seiðr”) ends up overseeing the cult to her brother, Freyr (who is associated with elves), even as he lies in the burial mound. The people bring offerings to the mound for peace and good seasons, and so even in death, he possesses a power that his sister does not.

Wilby’s period of study. Hall traces a pattern of witches working with mound-connected elves from the tenth century Old English magico-medical charm Wið Færstice and term ælfs?den (literally “elf-Seiðr”, or “elf-magic”); to Martin Luther’s account of being “shot” by a neighborhood witch; and finally to Isobel Gowdie’s accounts of encountering the Queen of Elfhame in a mound and seeing elves fashioning the shot. I personally take it somewhat further and point to the portrayal of Frey and Freyja in the Ynglingasaga. Freyja as the sacrificial priestess (and as we know, goddess associated with the form of magic known as “Seiðr”) ends up overseeing the cult to her brother, Freyr (who is associated with elves), even as he lies in the burial mound. The people bring offerings to the mound for peace and good seasons, and so even in death, he possesses a power that his sister does not. ” The transfer of George was further complicated by the queen of the Lowlanders, who demanded that Goodwin stop attempting to have George as his own personal spirit. At first Goodwin was a little resistant, but the queen insisted that if he would not willingly show her this preference, he should never see any of the Lowlanders. She wanted to be his number-one contact with the spirit world. Goodwin had little choice but to agree to her terms. As a consolation, George agreed to answer any questions directed at him as long as Goodwin turned his back and did not look directly where George stood. However, Goodwin could not understand the spirit very clearly, as he spoke in a low, soft voice close to Mary’s ear. So throughout their relationship, Goodwin relied on Mary to communicate with George.”

” The transfer of George was further complicated by the queen of the Lowlanders, who demanded that Goodwin stop attempting to have George as his own personal spirit. At first Goodwin was a little resistant, but the queen insisted that if he would not willingly show her this preference, he should never see any of the Lowlanders. She wanted to be his number-one contact with the spirit world. Goodwin had little choice but to agree to her terms. As a consolation, George agreed to answer any questions directed at him as long as Goodwin turned his back and did not look directly where George stood. However, Goodwin could not understand the spirit very clearly, as he spoke in a low, soft voice close to Mary’s ear. So throughout their relationship, Goodwin relied on Mary to communicate with George.”