Breath is sacred to me. And not just because I rely on it to stay alive.

As a Heathen, breath was the first life-bringing gift given to humans in the poem Völuspá. These first humans (at least according to this mythological account) began their existence as “trees”. In Gylfaginning, these “trees” are found on a windswept beach, I imagine them as logs possibly washed up by the sea.

So three gods happen upon these dendrous layabouts, and decide to give  them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them.

them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them.

Just imagine for a moment – the cold and unyielding wood somehow coming to breathe. I have to imagine those first breaths to be creaking and harsh, possibly even painful.

But then comes Loðurr with what might have been heat and color. (I say ‘might’ here because there’s some discussion about the ‘heat’ part.) I now imagine the harshness of creaking wood softening to flesh, and those harsh gasps becoming sighs of relief.

It’s probably a kindness that Hœnir’s gift came last really. Because he gave them óðr or mind, and presumably only then, an awareness of self.

There’s a lot to be said about these gifts and their relevance to magic. Today though, I’m going mostly to focus on Óðinn’s gift of önd.

Breath and ‘Soul’

You may have already inferred from the retelling above that önd is breath, and it is. But önd wasn’t just speaking to the breath that oxygenates the body. In both the Zoega and Cleasby-Vigfusson dictionaries, it is also translated as ‘soul’ too.

For me though, önd is also the steed upon which inspiration, or óðr rides. A fitting gift from the god of Skalds.

The Nature of Inspiration

But before we follow that thread any further, we first need to take a look at what inspiration may have originally been.

Unfortunately, the Norse and Germanic corpus isn’t particularly forthcoming on the nature of inspiration. We know that there are poetic meters associated  with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>).

with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>).

However, in my opinion, our best clues come from the Welsh sources.

Like the Norse, the Welsh had an advanced culture of poetry (as too did the Irish). To be a poet, was to be capable of magic, and poets possessed of awen had the ability to influence kings.

The Welsh word awen, or ‘poetic genius’ carried supernatural and magical connotations, and was associated with spiritual enlightenment and wisdom. This was not “inspiration” as we know it today. This was inspiration associated with ideas of ‘spiritual wind’ and ‘divine breath’. The words ‘awen’ and awel (a Welsh word meaning ‘wind’ or ‘breeze’) are both derived from the Indo-European *uel, or ‘breath’. (You can find out more about awen in this video by Welsh scholar, Dr Gwilym Morus-Baird here.)

But it’s when we get to the purported origin of awen that things become interesting. Because in the Welsh sources, awen comes from the Welsh Otherworld, or Annwfn, the ‘Very Deep World’, rising up as a ‘spiritual wind’ or  ‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts.

‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts.

As one might expect of the ‘Very Deep World’, Annwfn is often depicted as a chthonic realm in the medieval Welsh texts – an underworld, if you will. It is a realm connected with spirits, both Otherworldly and dead alike. An idyllic realm, a perfected realm. And it’s here with this idea of inspiration that comes from spirits and is breathed in (inspired) where we come crashing back into the Norse sources.

The topic of spirits entering a person for prophecy or other purposes can be quite controversial in modern Heathenism – taboo in some circles even. But as Eldar Heide demonstrates in Spirits Through Respiratory Passages , there is ample evidence of spirits entering a person through the breath. The evidence presented by Heide in the paper is primarily concerned with hostile attacking spirits who enter by forcing a yawn in their victims and enter on the in-breath. But an example given from Hrólfs saga kraka, shows that ingress by spirits may have also been a part of seiðr. In the account given in Hrólfs saga kraka, a seiðkona is depicted yawning before giving (or attempting to give) prophetic answers. Moreover, it was not uncommon This occurs multiple times in the account. Could this be a potential parallel to the awen-filled speech of the Welsh poets?

Working with Breath

In the magico-religious practices that I’ve developed over the years, breath is one of the key ways through which I connect with Óðinn. For many people who work with this god, he is called Allfather because of his role in enlivening Askr and Embla. However, for me, he is the Allfather because as the giver of breath, he is the giver of the one gift that all humans share regardless of ethnicity. We all breathe from the same air when we take our first breaths as newborn infants, and our final breaths will leave us to mingle once more with the winds. This is one of the main ways in which we are all connected, and it is with that understanding that I explore the breath in my work.

Meditation

There are many ways in which you can work with breath in Heathen magic and magic in general. But today I’m going to begin with meditation.

Many types of meditation work with the breath. Usually, it is used as a vehicle for changing one’s mental state and/or as a focus or support for meditation. But breath can also be used as a medium for exploring that sense of interconnectedness I mentioned above.

The first time I experienced this, I was stood at the side of Goðafoss waterfall  in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them.

in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them.

It is this experience I try to replicate when I meditate in this way. I begin with offerings and a prayer before taking a few moments to calm myself and fall into a light trance state. Then I focus on my breath as a connecting medium. Each time I breathe in, I do so with the awareness that I am breathing in a substance of winds, spirits and inspiration shared by everybeing else that breathes as I do. Then I release it back into the wholeness of the world completing the circle once more. Each breath is a micro-reenactment of life from birth to death. On good days, I focus so completely on the breath and what it carries that I no longer feel the separation between myself and the whole, and that is when the real magic happens.

In my experience, this exercise is the most satisfying when performed in a high place where the winds blow free, but you do not need to be on a mountaintop to do this. Your backyard or sitting indoors near an open window will work just as well.

A Story in Parts

In this post, we’ve covered a lot of ground. We began in mythological time, with three gods on a windswept beach giving life to the first humans, and followed the breath to its connections with spirit-gotten inspiration in the Welsh tradition before returning to the North and the theme of spirits through respiratory passages. Those of you who are more familiar with the ON material will have probably noticed that the more typical word for both ‘inspiration’ and possibly also ‘possession’ too. There is no doubt that there is some overlap here, but we’ll be getting into that further in the next post.

Speaking of the next post, we’re going to be taking a look at the other gifts of life, some of their most important uses in magic, and the possible connections between those gifts and the most common elements found in Old Norse magic. Well, at least as I see them.

Until we meet again, friends!

Be well.

living. But their visits also brought sickness, and that’s just what they brought to the people of a place called Frodis-water.

living. But their visits also brought sickness, and that’s just what they brought to the people of a place called Frodis-water. some of those laws might be. I am going to infer one right now: that our rights to this world are lost when we breathe our last.

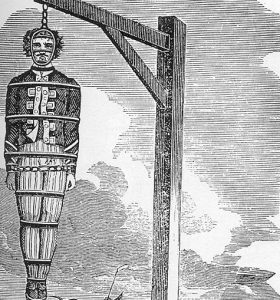

some of those laws might be. I am going to infer one right now: that our rights to this world are lost when we breathe our last. The story of the door-courts suggests that both living and dead are equally bound by the law. We also see this reflected in the burial customs of those deemed to exist outside the protection of the law. These were often the criminals left to rot at the crossroads, those buried in unhallowed grounds, and those who were too young at the time of their passing to be formally accepted in a community (Petreman “Preturnatural Usage”). Is it any coincidence that the materia magica sought from the human body came most often from these sources? Is it also coincidence that those were the sources thought by the Ancient Greeks to carry the least miasma (Retief “Burial”)? To exist as dead inside the protection of the law is to sleep soundly – or at least it should mean that. Of course, there have always been violations as Burke and Hare could well attest.

The story of the door-courts suggests that both living and dead are equally bound by the law. We also see this reflected in the burial customs of those deemed to exist outside the protection of the law. These were often the criminals left to rot at the crossroads, those buried in unhallowed grounds, and those who were too young at the time of their passing to be formally accepted in a community (Petreman “Preturnatural Usage”). Is it any coincidence that the materia magica sought from the human body came most often from these sources? Is it also coincidence that those were the sources thought by the Ancient Greeks to carry the least miasma (Retief “Burial”)? To exist as dead inside the protection of the law is to sleep soundly – or at least it should mean that. Of course, there have always been violations as Burke and Hare could well attest. the holy powers, but fire also played an important role in property ownership too. For the Norse, carrying fire sunwise around land you wished to own was one method of claiming that land (LeCouteux 89), and under Vedic law new territory was legally incorporated through the construction of a hearth. This was a temporary form of possession too, with that possession being entirely dependent on the ability or willingness of the residents to maintain the hearthfire. For example, evidence from the Romanian Celts suggests that the voluntary abandonment of a place was also accompanied by the deliberate deconstruction of the hearth. And the Roman state conflated the fidelity of the Vestal Virgins to their fire tending duties with the ability of the Roman state to maintain its sovereignty. The concept of hearth as center of the home and sign of property ownership continued into later Welsh laws too; a squatter only gained property rights in a place when a fire had burned on his hearth and smoke come from the chimney (Serith 2007, 71).

the holy powers, but fire also played an important role in property ownership too. For the Norse, carrying fire sunwise around land you wished to own was one method of claiming that land (LeCouteux 89), and under Vedic law new territory was legally incorporated through the construction of a hearth. This was a temporary form of possession too, with that possession being entirely dependent on the ability or willingness of the residents to maintain the hearthfire. For example, evidence from the Romanian Celts suggests that the voluntary abandonment of a place was also accompanied by the deliberate deconstruction of the hearth. And the Roman state conflated the fidelity of the Vestal Virgins to their fire tending duties with the ability of the Roman state to maintain its sovereignty. The concept of hearth as center of the home and sign of property ownership continued into later Welsh laws too; a squatter only gained property rights in a place when a fire had burned on his hearth and smoke come from the chimney (Serith 2007, 71). fires burning. To maintain the hearth was to maintain possession of property, and to maintain the hearth, a woman was required. (Or several, if you happen to be the Roman state.)

fires burning. To maintain the hearth was to maintain possession of property, and to maintain the hearth, a woman was required. (Or several, if you happen to be the Roman state.)

Greenville, South Carolina. Over the course of the next week, a further five sightings were reported to the local police department. Those of us who didn’t live in Greenville, especially those of us raised on Stephen King’s IT, were relieved to not be there. Over the course of the coming weeks,

Greenville, South Carolina. Over the course of the next week, a further five sightings were reported to the local police department. Those of us who didn’t live in Greenville, especially those of us raised on Stephen King’s IT, were relieved to not be there. Over the course of the coming weeks,  started to become so prominent. Some people pointed out the

started to become so prominent. Some people pointed out the  the commedia, as their antics and intrigues decided the fate of frustrated lovers, disagreeable vecchi, and each other. Perhaps best known of these is Arlecchino, or Harlequin (1974.356.525), a character whose origin is contested. It is likely that he derived either from Alichino, a demon from Dante’s Inferno (XXI-XXIII), or from Hellequin, a character from French Passion plays, also a demon charged with driving damned souls into Hell. Arlecchino is characterized as a poor man, often from Bergamo, whose diamond-patterned costume suggests that he is wearing patchwork, a sign of his poverty. His mask is either speckled with warts or shaped like the face of a monkey, cat, or pig, and he often carries a batacchio, or slapstick.”(4) (Emphasis is my own.)

the commedia, as their antics and intrigues decided the fate of frustrated lovers, disagreeable vecchi, and each other. Perhaps best known of these is Arlecchino, or Harlequin (1974.356.525), a character whose origin is contested. It is likely that he derived either from Alichino, a demon from Dante’s Inferno (XXI-XXIII), or from Hellequin, a character from French Passion plays, also a demon charged with driving damned souls into Hell. Arlecchino is characterized as a poor man, often from Bergamo, whose diamond-patterned costume suggests that he is wearing patchwork, a sign of his poverty. His mask is either speckled with warts or shaped like the face of a monkey, cat, or pig, and he often carries a batacchio, or slapstick.”(4) (Emphasis is my own.)

becoming somewhat clearer now. But I do not believe that this principle applies solely to the dead, and that we can see a form of this kind of embodiment of the ‘more-than-natural’ in some of the sources on shapeshifting too. For example, Sigmund and Sinfjötli of the Volsunga Saga become wolves through the donning of skins, and this theme survived into the 17th century when Thiess the self-described werewolf of Livonia testified that he and his fellow werewolves [on their journey to hell to retrieve seeds stolen by a sorcerer called Skeistan] had to strip off and don skins. (10)

becoming somewhat clearer now. But I do not believe that this principle applies solely to the dead, and that we can see a form of this kind of embodiment of the ‘more-than-natural’ in some of the sources on shapeshifting too. For example, Sigmund and Sinfjötli of the Volsunga Saga become wolves through the donning of skins, and this theme survived into the 17th century when Thiess the self-described werewolf of Livonia testified that he and his fellow werewolves [on their journey to hell to retrieve seeds stolen by a sorcerer called Skeistan] had to strip off and don skins. (10)