Furious Witch is Furious

The first time I cursed someone by accident I was angry. No, scrub that – I was furious. It was the kind of rage that heats the blood and causes the body to shake, to drive that pre-fight shot of adrenaline up the spine. And before I knew it the words had taken flight from my tongue, fully formed before I had even realized they’d been marshalled and ready to depart.

I’d felt it too at the time. There was the sensation of something leaving,  something being unleashed into the world, and I knew then and there that what I had spoken into the world would come to pass; that my victim would fall from his ladder at work.

something being unleashed into the world, and I knew then and there that what I had spoken into the world would come to pass; that my victim would fall from his ladder at work.

I remember then rushing to work protective magic on the person I’d cursed. You see, I didn’t really hate them, and I really didn’t want them to be hurt either. I was still young in my craft back then and my fury had been the one in the driving seat.

The next day the target of my wrath experienced the effects of both my curse and protection. He fell from his ladder at work while cleaning the top floor windows of a house and walked away completely unharmed. His boss was so shook up by the entire thing he gave him the rest of the day off anyway and sent him home.

This isn’t a boast. If anything, I’m not particularly proud of this moment. There is no ‘win’ here, just a loss of control that could have potentially seriously hurt someone I didn’t actually want to hurt. But it is a memory that has been coming up of late as I’ve been digging into the relationship between inspiration, fury/frenzy, and charms.

Furious Gods, Inspired Gods

As both a writer and magic worker, inspiration forms an integral part of my practice. In my fiction I birth new characters, and commit to word the speech of beings who I am fairly sure existed long before my birth and who will still exist long after I am gone. In magic…well, maybe in another post (this one is super long).

I’ve written about Óðinn/Woden here before, of his wisdom and relationship to breath. Without a doubt he is the god who has had the greatest influence over my life, answering my prayers and gifting to me in return in every land I’ve ever lived. But there is one element of this god that hasn’t really made sense to me until relatively recently, and that is the collocation between fury/frenzy and inspiration.

Óðinn’s connection with the poetic (and by extension, the inspiration that makes poetry possible) is quite well established in the lore. In Skáldskaparmál, it is Óðinn – or as he is also known, Fimbulþulr (Mighty Poet/Mighty Speaker) – who steals Óðroerir, or the ‘mead of inspiration/poetry’ from the giant Suttung (Price 63). It is because of him (at least according to the Prose Edda), that any of us even have any poetic ability at all (even the bad poets, who apparently are the recipients of the mead Óðinn shat out while escaping Suttung – seriously, look it up!). Yet as the myth makes clear, he is not the source of inspiration but its liberator – he too had to acquire it.

Óðinn’s association with the poetic and inspired seems to have persisted outside the mythical realm as well. In the sagas we find the famous Viking Age poet Egill Skallagrímsson, the protagonist of Egils Saga. Egill was a quintessentially Odinic figure, a warrior-poet who had knowledge of runes, was possessed of a berserker’s wrath, and carried one of Óðinn’s heiti as a compound in his name (Grímr).

Further possible support for a connection between Óðinn and poets comes from more modern criticism of the Eddas and the worldview they present (that of Óðinn as the head god who presides over a Norse pantheon). For these critics, this is a skewed perspective that was likely unknown to people who lived away from the centers of power that arose during the migration period, the ruling elites that inhabited them, and the poets they patronized. After all, what was a ruler back then without a poet to provide PR?

This is the core of the argument that scholar Terry Gunnell makes in Pantheon? What Pantheon? and From One High One to Another: The Acceptance of Óðinn as Preparation for God. For Gunnell, it is potentially thanks to the poets – those purveyors of Óðinn-centric religion – that the Eddas and the skáldic corpus survived in later years. The art of poetry was valued by both Heathen and Christian alike, and these sources may have been used as skáldic teaching texts therefore justifying their preservation.

Of course, an easy counterargument to this theory would be that the god of poets in the Eddas was Bragi and that the Óðinnic focus of the skálds could be easily explained by the necessity of pleasing their Óðinn-worshipping patrons. However, we should also note the inclusion of poetic meters such as galdralag (magic spell meter), and as Magnus Olsen argued, even dróttkvætt in magical charms – an area with which Óðinn is far more securely associated (Simek 98; Olsen 1916, “On Magical Runes”).

But we’ll get to that later. First, we need to embrace the fury.

Woden id est Furor

Writing in Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae Pontificum IV, the German chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote of Woden, Woden id est furor, or “Woden, that is to say fury” (Simek 1993, 242). This is probably the most well known reference to Woden or Óðinn’s furious tendencies, but it isn’t by any means the only one. We’re going to return to this phrase and the other possible translations of the Latin word fūror later, but a translation of “fury” or “frenzy” is sufficiently complete for now.

is sufficiently complete for now.

Although best known as Óðinn (a name which may be translated as “Frenzied/Furious One”), the deity we mostly call “Óðinn” is a god of many names or heiti. In The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia, Neil Price lists roughly 180 different heiti for the One Eyed God (depending on how you count them), which he divides thematically into 17 different categories. In the ‘Frenzy-, trance- and anger’ category, Price counts no fewer than 22 heiti or 10.5% of all heiti listed (including the name Óðinn itself) (Price 63 – 68).

Woden id est furor indeed!

What’s in a Name?

One of the most amusing things to me as a long-time worshipper of Óðinn is the tendency for those (usually on the far right) to see him as some unyielding, hypermasculine force. And as I’ve argued before, often the associations they place upon Óðinn are far more reflective of their own ideas about leadership and masculinity as opposed to what we find in the source material.

The etymology of Óðinn/Woden/Wodan/Wuotan/Wuodan (as they are all phonetic variants of the same name), is another area I believe further disproves this idea of the One Eyed God (Liberman, “Wednesday’s Father”). Not that that’s the point of this essay, but I may as well mention it while I’m here.

The name Óðinn is related to the ON adjective óðr, a word that translates as “frantic” or “furious”. In turn, óðr is believed to derive from the Proto-Germanic *wōda, a word meaning “delirious”. Also derived from *wōda and related to the ON óðr are the Gothic wods (“possessed”), OE wod (“insane”), and the now obsolete Dutch word woed meaning “frantic”, “wild”, or “crazy”.

Generally speaking, the further you trace an etymology back, the less secure and more theoretical that etymology becomes. If you notice, I used the term “believed to derive from” when referring to the Proto-Germanic root of óðr. This is because etymology at this time depth largely relies on words that are reconstructed using a series of educated guesses about things like sound changes. Words that are reconstructed in this way are written with an asterisk (*) at the beginning so as to clearly delineate them as linguistic reconstructions.

When you do trace that etymology back further to the WEUR (Germanic/Italo-Celtic) root *uoh2-tó though, you also arrive at the root of a number of Celtic language terms related to prophecy and soothsaying such as the OIr fáith (“soothsayer, prophet”), fáth (“prophesy”), and the Welsh word gwawd (“poem, satire”).

Interestingly, despite the degrees of linguistic separation that stand between the Celtic descendants of that WEUR root and ON óðr, the meanings of the noun óðr occupy a surprisingly similar semantic field as their Celtic counterparts on the other side of the language tree. As a noun, óðr may be translated as “mind”, “feeling”, “song”, and “poetry”. This is the óðr that is the third of the life-giving gifts to Askr and Embla.

All words for mutable, intangible qualities bobbing around in the shifting sands of etymology, but a remarkably consistent picture all the same.

Furor?

Which brings us quite neatly back to the Latin word fūror. Because although you only ever usually see it translated as “fury” or “frenzy” within the context of Woden, the word fūror carries a number of other meanings that make Adam’s choice of descriptor really quite accurate.

According to Cassell’s Latin & English Dictionary (1987, 98), the word fūror may be translated in the following way:

Fūror: madness, raving, insanity, furious anger, martial rage; passionate love; inspiration, poetic or prophetic frenzy…

Once again, even with a word most commonly translated as “fury”, when we dig down further, we find that same collocation of fury, frenzy, poetry and prophecy as we saw in the etymology of óðr and its various linguistic relatives given in the section above.

Charm Father

As mentioned above, the art of the poet could also be turned towards the sorcerer’s art – there was even an entire poetic meter for writing spells (galdralag). Unlike with poetry however, Óðinn’s position as galdrs föður, or  “Father of Galdr” (as he was named in Baldrs Draumar) is both explicit and well-established, and not just in the ON sources either (Simek 242). Woden is the only Heathen god to be mentioned in the OE magico-medical manuscripts; it is he who rests at the center of the so-called “Nine Herbs Charm” found in the Lacnunga. And it is Woden who is depicted chanting a spell over an injured horse’s leg in the Second Merseburg Charm (Waggoner, xv).

“Father of Galdr” (as he was named in Baldrs Draumar) is both explicit and well-established, and not just in the ON sources either (Simek 242). Woden is the only Heathen god to be mentioned in the OE magico-medical manuscripts; it is he who rests at the center of the so-called “Nine Herbs Charm” found in the Lacnunga. And it is Woden who is depicted chanting a spell over an injured horse’s leg in the Second Merseburg Charm (Waggoner, xv).

In my opinion, it is noteworthy that it is Óðinn who features in two of the most well known healing charms, especially given the normally combative nature of magical healing in Germanic cultures. Sickness was often perceived as being an invading force – often personified in some way -to be driven out or defeated, rendering the healer a magical warrior of sorts (Storms 49-54).

And this is where the various pieces of information laid out in this post begin to coalesce.

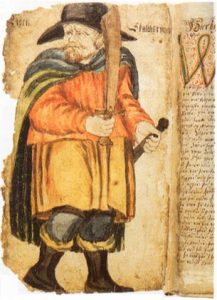

Enter The Tietäjä

For the final part of our exploration of fury, inspiration, and charms, we’re going to leave behind the Old Norse world and move eastwards and forwards in time to the lands of the Finnish magical specialist, the tietäjä (“knower, one who knows”).

The first written record of a tietäjä is relatively late, dating back to the 18th century at the earliest, However there is evidence to suggest that the “technology of incantations” that form the basis of the tietäjä’s interactions with the unseen world was adapted into North Finnic traditions from Germanic cultural influences during the Iron Age (Frog. “Shamans, Christians, and Things”).

That is not to say that the tietäjä somehow belongs to the Germanic cultural

sphere though. If scholars such as Anna Leena Siikala are correct in their assertion that the ‘tietäjä institution’ took shape in the first millennium CE, then there have been at least hundreds of years of Finnish cultural adaptation of this “technology of incantations” despite its Germanic roots (Frog. “Shamans, Christians, and Things”). Rather than looking at the tietäjä’s art as a wholesale survival of Germanic charm magic, it is the potential echoes of those older Germanic “technology of incantations” that interest us.

Throughout the course of this essay we’ve focused on the figure of Óðinn and the seeming paradox of a god of charms who is associated with poets, inspiration, fury, frenzy, madness, and berserkers (remember Egill?). I believe these characteristics provide the best clue to those older Germanic echoes that survived in the tietäjä’s art. Moreover, I believe that through examining accounts of tietäjäs (some of them from the perspective of the tietäjäs themselves) – especially where behavior is concerned – can provide important insight into working with Germanic charm material in the modern day.

The Tietäjä’s Body and Behavior

According to the account of a tietäjä recorded in 1835, the tietäjä had to possess “terrible luonto (inner supernatural force)” and anger in order to perform a charm successfully. The theme of extreme anger and violence is one that is often conveyed both in the ritual actions of the tietäjä as well as embodied by the tietäjä himself while working his magic. It is not enough to just feel enraged, one must act like it too.

Of the tietäjä’s behavior, Finnish folklorist Elias Lönnrot gives the following summary:

“the tietäjä 1) becomes enraged, 2) his speech becomes loud and frenzied, 3) he foams at the mouth, 4) gnashes his teeth, 5) his hair stands on end, 6) his eyes widen, 7) he knits his brows, 8) he spits often, 9) his body contorts, 10) he stamps his feet, 11) he jumps up and down on the floor, and 12) makes many other gestures.”

-taken from Laura Stark, The Charmer’s Body and Behavior in Charms, Charmers and Charming

For the tietäjä, fury was a source of power, and as such people took great pains to avoid incurring the wrath of a tietäjä. In one story an old tietäjä becomes so angry at a farmhand who unwittingly vandalizes his bird-trap that the farmhand goes insane. And when asked if the farmhand could be spared his fate, the old sorcerer simply tells them that it’s impossible as he became “too angry” (presumably while working his magic) (Stark, 8).

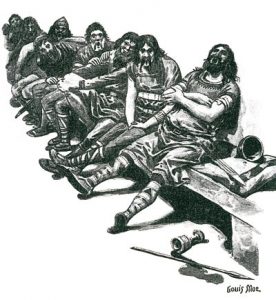

A Berserker and a Tietäjä Walked into a Bar…

There are also some interesting parallels between the tietäjä and ON berserkr here as well. Though the behavior is more extreme in the following account (a depiction of the berserker’s famous imperviousness to fire and iron), there are still notable parallels between this account and the list of behaviors compiled by Lönnrot.

“These men asked Halfdan to attack Hardbeen and his champions man by man; and he not only promised to fight, but assured himself the victory with most confident words. When Hardbeen heard this, a demoniacal frenzy suddenly took him; he furiously bit and devoured the edges of his shield; he kept gulping down fiery coals; he snatched live embers in his mouth and let them pass down into his entrails; he rushed through the perils of crackling fires; and at last, when he had raved through every sort of madness, he turned his sword with raging hand against the hearts of six of his champions. It is doubtful whether this madness came from thirst for battle or natural ferocity.”

“These men asked Halfdan to attack Hardbeen and his champions man by man; and he not only promised to fight, but assured himself the victory with most confident words. When Hardbeen heard this, a demoniacal frenzy suddenly took him; he furiously bit and devoured the edges of his shield; he kept gulping down fiery coals; he snatched live embers in his mouth and let them pass down into his entrails; he rushed through the perils of crackling fires; and at last, when he had raved through every sort of madness, he turned his sword with raging hand against the hearts of six of his champions. It is doubtful whether this madness came from thirst for battle or natural ferocity.”

-Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum Book VII.

Like the berserker, the tietäjä was also said to be impervious to fire and iron ( Stark, 9). There was a belief that the tietäjä had to “harden” his body, making it impervious to both magical and physical damage.This “hardness” was not only dependent on the tietäjä’s inherent qualities (such as a “hard” or “strong” luonto), but could also be achieved through incantation and ritual as well.

Hardening the Body

Much like ourselves, tietäjäs also seem to have made use of magical shielding. But whereas modern practitioners might set themselves inside a magical bubble, the tietäjä seems to have called down protection from holy powers in the form of magical iron clothing or armor.

Give to me an iron coat,

Iron coat, iron cap,

Iron mantle for my shoulders,

Iron mittens for my hands,

Iron boots for my feet,

With which I shall enter the Hiisi’s lands,

Move about in Evil’s realm,

So that the sorcerer’s arrows will not penetrate,

Nor the wizard’s knives,

Nor the shooter’s weapons,

Nor the tietäjä’s blades

(Stark, 8)

The tietäjä who was summoned to war was said to be bulletproof – “hardened” by wearing a shirt in which a corpse had been buried, or by holding a bullet that had killed someone in the mouth. One former soldier by the name of Alatt claims to have “brushed handfuls of bullets off his chest when they didn’t penetrate his skin” (Stark, 9).

Conversely, we do not know what rituals (if any) were performed by berserkers (though there have been plenty of theories suggested over the years).

Conclusions and a Question

At the beginning of this essay I began with a story of rage and magic. Of what rage can do, and what can (almost) happen when it’s allowed to burn out of control. Over the course of this study, we’ve looked at Óðinn’s seemingly disparate associations with poets, poetry, charms, frenzy and fury. We’ve dug into his heiti as well as the etymology of his name, and a surprisingly consistent collection of characteristics have emerged. From there, we shifted focus to the tietäjä and the ways in which they embodied many of those characteristics while working their charms and incantations (themselves a form of poetry). Finally, we looked at the similarities between tietäjäs and berserkers and methods used by tietäjäs to “harden” their bodies against physical and magical attack.

Though the tietäjä institution is undoubtedly Finnish, there seem to be some distinctly Óðinnic echoes here. It’s my opinion that the tietäjä’s use of fury as a source of magical power may be seen as a model for not only understanding Óðinn’s fury, but also the potential role of that kind of weaponized fury in galdr.

However, despite the meaning of his name or the 10.5% of heiti pertaining to frenzy, we never actually see Óðinn in the kind of berserker rage that is so associated with him (at least not in any sources that I can think of).

Rage is powerful – it is a source of power when chanting spells – yet without control it is just as easily our undoing as our success. The berserker wielded rage without control, becoming a danger to not only his enemies but his allies too, and was often outcast for it. The tietäjä wielded rage with control, but still often fell into the trap of becoming petty and punitive, and in some cases dooming entire families with their incantations (Stark, 11). Yet the “furious” god of many names does not seem to rage but remains the “Father of Charms”.

Now why do you think that is?

Sources

Cassell’s Latin & English Dictionary (1987)

Frog – Shamans, Christians, and Things in between: From Finnic–Germanic Contacts to the Conversion of Karelia

Grammaticus, Saxo – Gesta Danorum Book VII

Gunnell, Terry – From One High One to Another: The Acceptance of Óðinn as Preparation for God

Gunnell, Terry – Pantheon? What Pantheon?

Kroonen, Guus – Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic

Liberman, Anatoly – “Wednesday’s Child”, OUP Blog

Olsen, Magnus – On Magical Runes

Price, Neil – The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia (2nd Ed.)

Simek, Rudolf – Dictionary of Northern Mythology

Stark, Laura – “The Charmer’s Body and Behavior as a Window Onto Early Modern Selfhood”, in Roper, Jonathan (Ed.) Charms, Charmers and Charming: International Research on Verbal Magic

Storms, Godfrid – Anglo-Saxon Magic

Waggoner, Ben – Norse Magical and Herbal Healing: A Medical Book from Medieval Iceland

them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them.

them life. And this is where Óðinn steps up and breathes önd into them. with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>).

with magic and necromancy. And we can infer that Skaldic craft was itself considered magical. We can also look at the story of Egill Skallagrimson covering his head with his cloak in order to compose poetry in Egill’s saga, and possibly infer certain practices related to the getting of inspiration (as Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson theorizes in <em> Going Under the Cloak</em>). ‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts.

‘divine breath’ to fill the poet, bringing vision and other spiritual gifts. in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them.

in Northern Iceland. I’d just been under the cloak and was thinking about the stories surrounding the falls when I found myself wondering about Óðinn in Iceland. Suddenly, my attention was drawn to the sound of heavy wing beats that somehow sounded louder than the roar of the waterfall. Two ravens were flying across the width of the falls and their wings were all I could hear. Time became weighty and the world more ‘real’. I became intensely aware of my breath, and suddenly I was not just myself anymore but engaging in a communion of sorts with the winds, the world around, and a certain one-eyed god. I was a part of the whole rather than a singular being. The ravens turned and flew towards me until they drew level and veered away, taking the moment with them. I walk. I hear the rush of the water and feel the wind beating against my ears.

I walk. I hear the rush of the water and feel the wind beating against my ears. Christian alike.

Christian alike. practices like that though, if I’m being honest.)

practices like that though, if I’m being honest.) in my heart even, and search them out with my eyes.

in my heart even, and search them out with my eyes. too.

too.