In the first part of this post, I discussed the importance of dream, the various kinds of beings that were thought to attack sleepers, and what symptoms of those attacks were thought to look like in OE sources. In this part, I’m going to discuss the charms themselves and how we can use them in modern practice to hopefully sleep undisturbed.

Charms and Herbs: The Magico-Medical Prescription

The Old English charms are referred to as being magico-medical for good reason. Because unlike modern medicine which only seeks to treat the physical causes of disease, the Early English also recognized non-physical or”spiritual” causes of disease/illness, and tailored their treatments accordingly. So among the charms, you will find everything from recipes to treat physiological ailments, to charms that combined magical acts, verbal formulae, or both. Here follows a short overview of the relevant charms with analysis of the commonalities between the charms and how they may be used.

Bald’s Leechbook II, section 65, ff. 107v-108r – Wið ælfe 7 wiþ unc?þum s?dsan

This is one of the more general charms against elves and ‘strange/unusual’ s?dsa, or “magic” (again, cognate with “Seiðr”). Kitson suggests that the ingredients of this charm betray a foreign origin for the charm, but one that has been adapted to native tradition (Hall 120).

Against an elf/against elves and against unknown/strange/unusual s?dsa, crumble myrrh into wine and the same amount of white frankincense and shave a piece of jet [the stone] into that wine, drink on three mornings, fasting at night, or nine, or twelve.

L?cnunga, section 29, ff. 137r -138r

This is the holy/blessed drink against ælfs?den and against all tribulations of the enemy (Hall 120-121)

I only include this title as a matter of interest and to add to the evidence demonstrating the collocation of ælfs?den with f?ondes costunga. I largely agree with Richard North in Heathen Gods in OE Literature that this is more of an exorcism charm that might have been employed against those considered to be ylfig or “engaged with an elf”. As such, further detail is not particularly relevant for the purposes of this post.

Leechbook III, section 41, ff. 120v-121r: Wyrc g?de sealfe wiþ f?ondes costunga

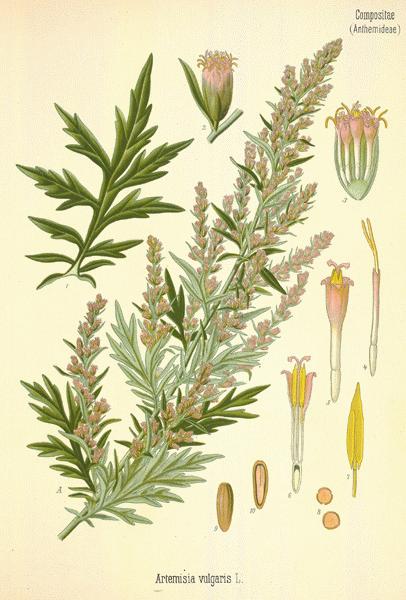

Make a good salve against the tribulations of the enemy: bishopwort, lupin, viper’s bugloss,

strawberry stalk, the cloved lesser celandine, eorðr?ma, blackberry, pennyroyal, wormwood, pound all those plants; boil in good butter, strain through a cloth; place under the altar; sing nine masses over them; then smear  the person with it generously on the temples, and above the eyes and on the top of the head and the breast and under the arms. This salve is good against each tribulation of the enemy and ælfs?den and Lent-illness.

the person with it generously on the temples, and above the eyes and on the top of the head and the breast and under the arms. This salve is good against each tribulation of the enemy and ælfs?den and Lent-illness.

Leechbook I, section 64, f. 52v: Læced?mas wiþ ælcre l?odr?nan 7 ælfs?denne

Prescriptions against every l?odr?ne and ælfs?den, being a charm, powder, drinks and a salve, for fevers: and if the illness should be upon livestock; and if the illness should happen to a person or a mære should ride and happen; in all 7 remedies

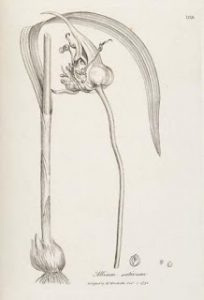

If a mære should ride a person: take lupin and garlic and betony and incense; bind in fawn-skin; the person should have this on him and he should walk wearing these plants

Leechbook III, section 61, f. 123: Wið ælfcynne

Make a salve against ælfcynne and a night-walker and for/against those people whom the devil has sex with: take hops(?), wormwood, bishopwort, lupin, vervain, henbane, h?rewyrt, viper’s bugloss, stalk of whortleberry, (?)crow garlic, garlic, seed of goosegrass, cockle and fennel. Put these plants in a vessel, place under an altar, sing 9 masses over them; boil in butter and in sheep’s fat; put in plenty of holy salt; strain through a cloth. Throw the plants into running water. If any evil tribulation or an ælf or a night-walker happens to a person, smear his face with this salve and put it on his eyes and where his body is sore/in pain, and burn incense about him and sign [with the cross] often; his problem will soon be better.

Make a salve against ælfcynne and a night-walker and for/against those people whom the devil has sex with: take hops(?), wormwood, bishopwort, lupin, vervain, henbane, h?rewyrt, viper’s bugloss, stalk of whortleberry, (?)crow garlic, garlic, seed of goosegrass, cockle and fennel. Put these plants in a vessel, place under an altar, sing 9 masses over them; boil in butter and in sheep’s fat; put in plenty of holy salt; strain through a cloth. Throw the plants into running water. If any evil tribulation or an ælf or a night-walker happens to a person, smear his face with this salve and put it on his eyes and where his body is sore/in pain, and burn incense about him and sign [with the cross] often; his problem will soon be better.

As you can see from the above charms, treatment/prevention of attack by maran/night-walkers/elves generally takes the form of a salve to be applied to certain parts of the body (but especially parts of the face). There are some commonalities in both the herbs and methodology employed, and while no one of the herb charms are one hundred percent clear, I believe it is possible to pull the most common herbs from these charms when recreating our own salves.

From these charms, bishopwort (betony), lupin (suggested to be lupinus albus), viper’s bugloss, wormwood, garlic, and some kind of berry stalk seem to be the most common. Most of them are also quite accessible to modern people. These herbs are then taken and made into a salve either before or after having 9 masses sung over them while positioned under the altar.

From my own survey of the use of numbers in the L?cnunga, the number 9 tends to be associated with banishing or driving out. So in order to create a ‘Heathenized’ version of this charm, I would simply ensure that the herbs I use for my salve would be under an altar during 9 rites of similar purpose to the mass. These would potentially be rites that combine aspects of consecration, seeking divine favor, and empowerment – in whatever form you’d like that to take for your tradition.

Equally, Leechbook I, section 64 suggests that a kind of amulet can be made that is not unlike a hoodoo hand. Again, we see the use of garlic, betony, and lupin. However, there is also the addition of ‘incense’ – which sounds quite vague until you look at other Leechbook cures in which incense is also a recommended. Interestingly, these cures (found in Leechbook III, section 62) also involve elves – more specifically how to cure forms of ‘elfsickness’.

In these charms, the healer is advised to prepare incense in a rather specific way and then burn it in the environment where the patient is in order to ‘smoke out’ the elf/illness. The instructions should look at least a little familiar by now.

Take a handful of each, bind all of the herbs in cloth, dip into hallowed spring-water three times. After this, against that (illness), lay these herbs under an altar and let them be sung over.

This suggests that this process of purification and laying under and altar is important to the success of the charm, and so I recommend that should you decide to try these charms, you find a way to incorporate this stage of purification/consecration and empowerment. As for the herbs for incense, I would recommend that you again choose from herbs mentioned previously in similar charms.

The Münchener Nachtsegen Charm

The following charm is not OE, but I include it here for its usefulness. Alb here means ‘elf’, and in Austria it was believed that the ‘alb’ was the soul of an evil woman under a spell by which she was compelled to leave her body and go out and torment people by night (LeCouteux 100)

Alb, or also elbelin [little alb]

you shall remain no longer

alb’s sister and father,

you shall go out over the gate;

alb’s mother,

trute [female monster] and mar,

you shall go out to the roof-ridge!

Let the mare not oppress me,

let the trute not pinche me

let the mare not ride me,

let the mare not mount me!

Alb with your crooked nose,

I forbid you to blow on [people]

(Hall 125-126)

Final Word

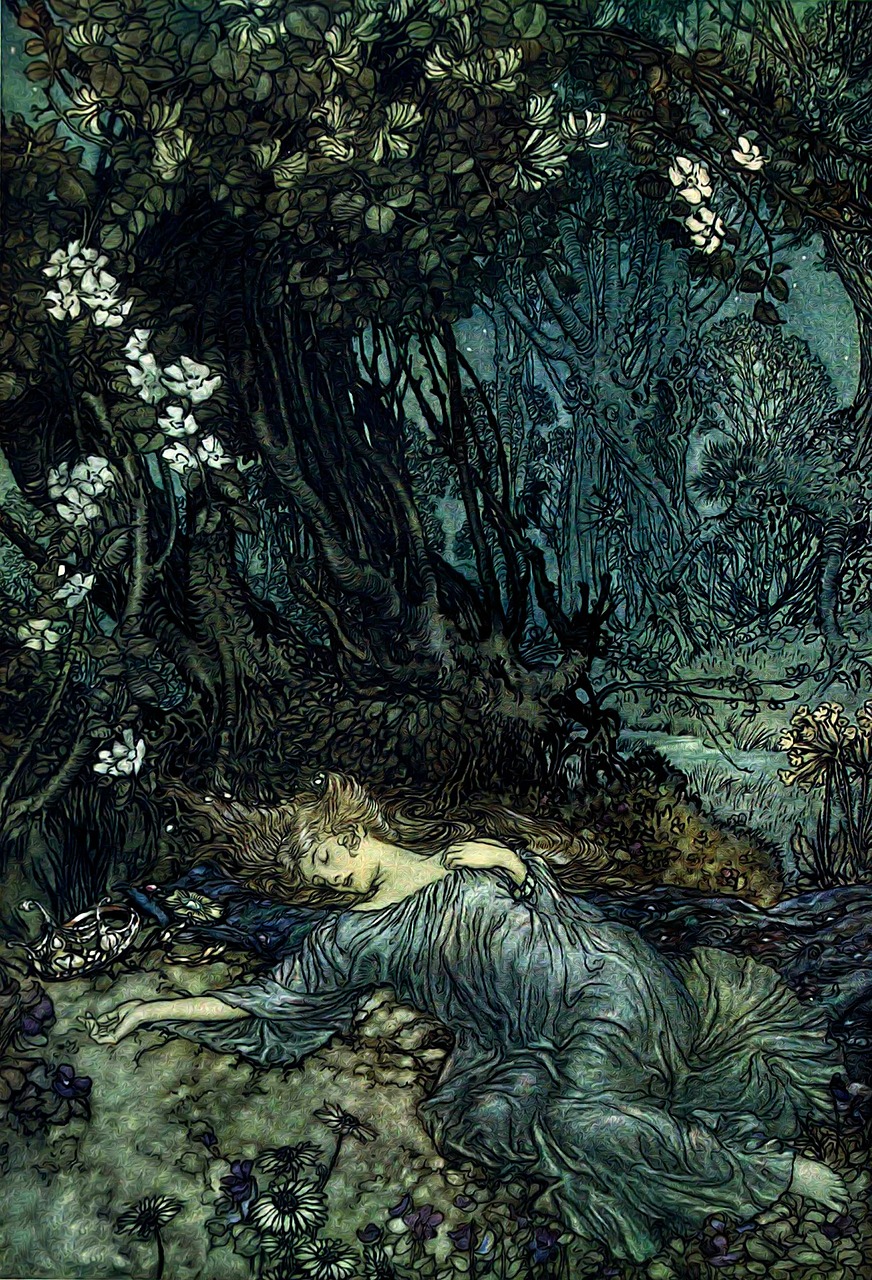

Hopefully the importance of dream to the Pagan/Heathen mindset has been made clear over the course of these past two posts. As I’ve written before, dream is something that I believe we need to fight for and reclaim.

However, few things as powerful as dream, come without any accompanying hazards. When we open these doors, when we invite in what was once chased back, we are often doing so half-blind. We have a lot of sources on various Heathen and Pagan worldviews, however none of them can tell us things like what it was to actually fear things like elves or faeries. None of them can tell us what it was actually like to live in such a populated and enchanted world; that is for us to [re]discover for ourselves. And there are few things more terrifying than the thought of being attacked by something that cannot be fought while already in a vulnerable state.

Sleep well!

Sources

Alaric Hall – Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity

Karen Jolly – Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context

Claude LeCouteux – Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages

Stephen Pollington – Leechcraft: Early English Charms, Plant-Lore and Healing

elves or night-goers need apply!), modern descriptions of this experience would have been familiar to our ancestors. In some accounts, such as that of the Swedish king Vanlandi of the Ynglinga saga, the victim was even “trod on” or “pressed down on” until dead. It is worth mentioning here that the attacking force was the witch/mara Drifa (Hall 125, 135). Interestingly, while the Ynglinga saga was composed post-conversion, a segment of the 9th century Ynglingatal referencing the death of king Vanlandi as a result of the witch (referred to in the Ynglingatal segment as mara) attests to the potential Heathen origins of this concept.

elves or night-goers need apply!), modern descriptions of this experience would have been familiar to our ancestors. In some accounts, such as that of the Swedish king Vanlandi of the Ynglinga saga, the victim was even “trod on” or “pressed down on” until dead. It is worth mentioning here that the attacking force was the witch/mara Drifa (Hall 125, 135). Interestingly, while the Ynglinga saga was composed post-conversion, a segment of the 9th century Ynglingatal referencing the death of king Vanlandi as a result of the witch (referred to in the Ynglingatal segment as mara) attests to the potential Heathen origins of this concept.