I think it was some time in the 2000s when I first noticed this kind of ‘anti-circle sentiment’ in the Pagan community. I was at an event, and someone who was clearly much smarter than I am had devolved into mocking me for still casting circles. It was a classic case of someone trying to score social capital at the expense of another, and as I was still new to interacting with other Pagans on a regular basis, I was far more timid in response than what I would be now.

Casting a circle had been declared both “Wiccan” and “fluffy”, and if John Beckett’s anecdote from his recent blog is anything to go by, circle-casting still suffers somewhat from this reputation. All the cool kids seem to find other ways to create sacred space within which to work. Moreover, even when a circle is cast, some will still refer to it by any other name.

But there’s a huge problem with this kind of mentality – well actually, there are two:

1. You’re basing your practice around trying to avoid being something as opposed to trying to figure out where that practice needs to go, and just going there.

2. You’re more focused on ideological purity and the opinion of others rather than what you’re actually doing.

Both of these issues can lead to some severe casting out of the proverbial baby with the bathwater, and that is what I believe has happened to the circle to some extent. Or at least, we don’t appreciate circles as much as we maybe should.

The History of the Circle

The magic circle is mostly associated with Wicca in modern Paganism, however, the use of magic circles predates Wicca by millennia. Scholar and practicing occultist, Professor Stephen Skinner, traces the earliest mention of protective floor circles to Classical Indian magic. The Ramayama (dating from 4th to 5th century BCE) describes the drawing of a circle on the ground to protect a person from a demon. When that person is persuaded to cross the circle, they are then taken by that demon (Skinner 79).

The circle could also be found among the Assyrians. Referred to as an u?urtu (“ring”), the Assyrian circle seems to have either been made with the intention of containment or protection. This is important to note, because although modern practitioners may give many different reasons for casting circles, and explanations of their function/s, in the ancient world the primary functions were that of containment and protection (Skinner 79).

Sometimes lime was used for marking out the Assyrian circle, and sometimes a mixture of water and flour (substances sacred to relevant Assyrian deities); both types of circle may be found in the sources. Once created though, it was then important that the circle was then consecrated with a charm such as this:

”Ban! Ban! [O] Barrier that none can pass,

Barrier of the gods, that none may break,

Barrier of heaven and earth that none can change,

Which no god may annul,

Nor god nor man can loose,

A snare without escape, set for evil,

A net whence none can issue forth,

spread for [against] evil.

Whether it be evil spirit, or evil demon, or evil ghost,

Or evil devil, or evil god, or evil fiend,

Or hag-demon, or ghoul, or robber-sprite,

Or phantom, or night-wraith, or handmaid of the phantom

Or evil plague, or fever sickness, or unclean disease

which have attacked the shining waters of Ea (the water from the water/flour mix),

May the snare of Ea catch it;

Or which hath assailed the meal of Nisaba (the flour from the water/flour mix),

May the net of Nisaba entrap it…” (Skinner 80)

I also include a Mesopotamian consecration charm here for its eminent usefulness and interest:

”We, therefore, in the names aforesaid, consecrate this piece of ground for our defence, so that no spirit whatsoever shall be able to break the boundaries, neither be able to cause injury nor detriment to any of us here assembled, but that they may be compelled to stand before this circle and answer truly our demands.” (Skinner 80)

Both consecration charms make it clear that at its core, the circle is a form of boundary or barrier through which nothing may pass if created correctly. By its very nature, it both contains and protects, this is the core function of a magic circle in the earliest sources – everything else is just gravy.

(Btw, if you do not already own Stephen Skinner’s Techniques of Graeco-Egyptian Magic, I cannot recommend it enough.)

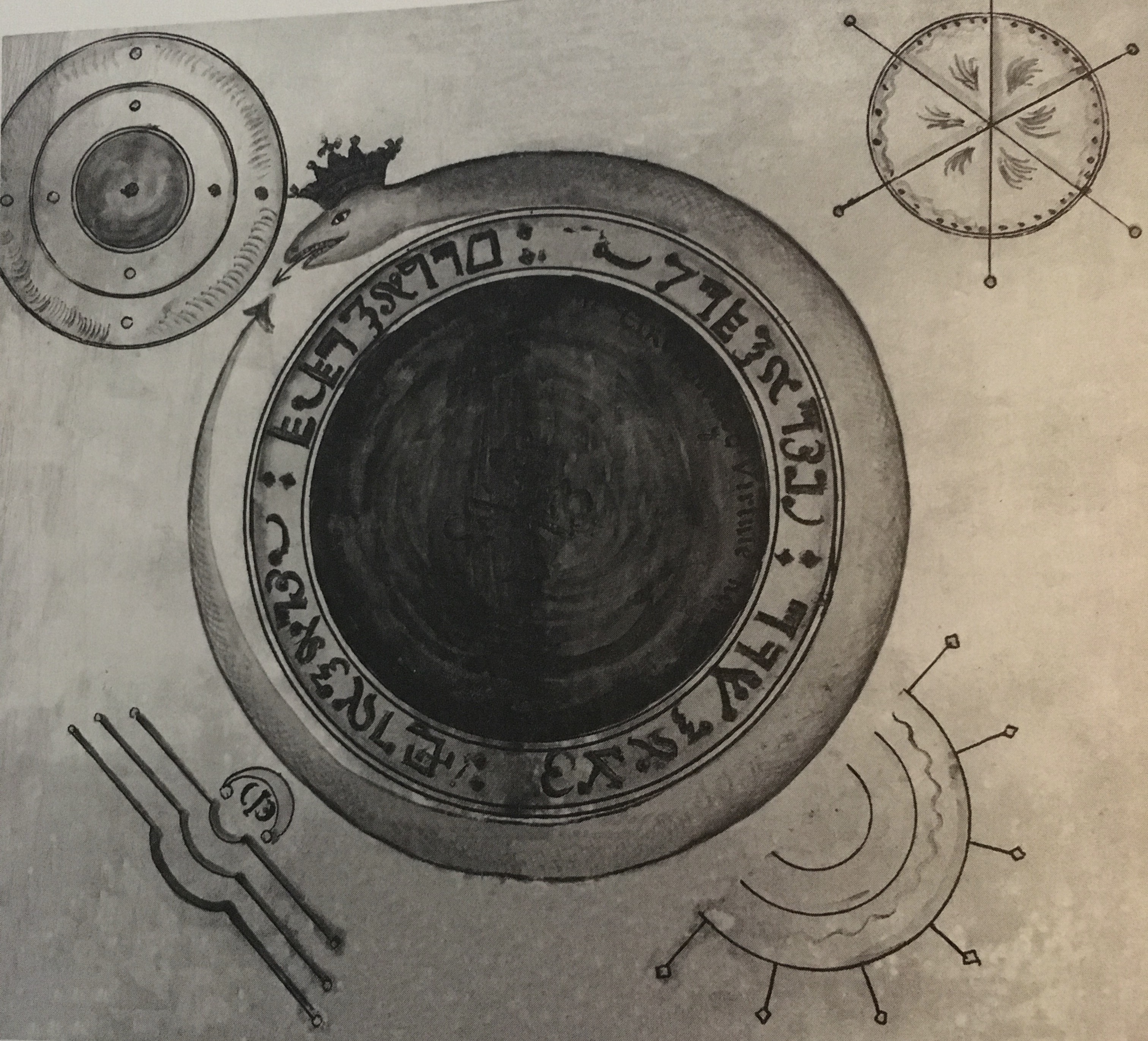

Circles, often in the form of an ouroboros, also feature in Egyptian depictions of magic – again as

this kind of impermeable barrier (Skinner 82-83). Skinner posits that although the ouroboros circle is only specifically mentioned twice in the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM), the creation of a circle was probably taken for  granted and covered by phrases such as “do the usual”. It is no coincidence that the ouroboros features in later grimoires such as the 18th century Clavis Inferni. Indeed, it’s likely that the use of a protective circle in the form of an ouroboros and directions marked out (and associated with elemental entities) were inherited magical tech from those old-school Graeco-Egyptian magicians (Skinner 87).

granted and covered by phrases such as “do the usual”. It is no coincidence that the ouroboros features in later grimoires such as the 18th century Clavis Inferni. Indeed, it’s likely that the use of a protective circle in the form of an ouroboros and directions marked out (and associated with elemental entities) were inherited magical tech from those old-school Graeco-Egyptian magicians (Skinner 87).

The Core Purpose and its Gravy

However, even the most cursory study of the ‘how’ of casting magic circles shows that there is no one way to cast a circle. Instead, there is variation and adaptation depending on any number of factors, including (but not limited to) the tradition of the practitioner, and the spirits being worked with. For example, in the Book of Oberon, different circles are given for different spirits. Unlike most modern circles, these circles were – like the Assyrian and Indian circles – meant to be drawn out on the ground usually using substances considered to have apotropaic properties either by virtue of the substance itself or by association with a deity/deities.

It would seem that a simple impermeable barrier is not enough though, and much may be included in either the design (when drawn physically) or circumambulation portion of circle casting (also important in the ancient sources).

However, variation is typically reflective of differing ideas about how the cosmos looks and/or the worldviews of the practitioners involved. Here we must not only consider the idea of the circle as barrier, but also the circle as and Eliade-esque “sacred center” and map of macrocosmic creation recreated in the microcosm.

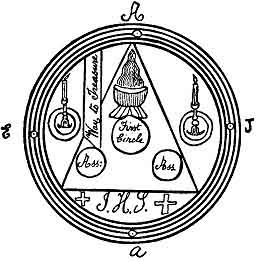

To give you an example of this, take a look at this goetic circle.

Well now take a look at this circle for the Luridan conjuration.

Just to give you some backstory here – Luridan was one of the spirits associated with the Icelandic volcano, Hekla (Stratton-Kent, Pp 68-71). But here we see a volcano placed in the usual spot for the censer. Now, your average magician isn’t going to manage to get a volcano in his or her circle (not unless you’re working on a scale that’s just completely unfeasible), so it’s logical to assume that within this circle the volcano is represented by the censer. In my opinion, this is a clear recreation of the part of the cosmos inhabited by the spirits the magician wishes to summon (and is a whole lot easier than going to Hekla for the same).

I mean, there’s also some local adaptation to old school chthonic Greek religion and Hephaestus stuff in there, but nifty, huh?

This is why circles are as long lived as they are. Because not only do they work, but they are customizable, meaning you can optimize to get better results if you understand enough of the underlying mechanics.

Pimping Your Circles

So, this is me proposing a more flexible view of creating sacred space. A view in which customization and optimization in order to get better results is a thing. For those of you who only work with the same spirits and within the same system, this is perhaps less useful to you. But for those of you who are like myself, total fucking magpies who straddle multiple systems like a fat cat spilling out into multiple boxes, read on.

If you are looking at ways to pimp your circles, or indeed create new ways of casting circles, then it’s a good idea to consider the following:

1. The Purpose of the Rite

The circle for a celebratory rite is not going to be the same as the circle for a rite summoning something potentially dangerous. For example, you’re going to be want to really focus on building that kickass barrier for the summoning, but the circle for a celebratory rite might see the circle mostly envisioned as a representation of the cycle of the year (just to give an example).

2. The Gods/Spirits Summoned

When summoning gods or spirits, you may like the Luridan conjuration, want to recreate the part of the cosmos associated with that god or spirit within the cosmology of the circle. Moreover, depending on *which* gods or spirits you summon, you may also have to incorporate things like spirit hierarchies and thwarting angels into the design of your circle. To return to the image from the Clavis Inferni above for a quick example of this, the symbols of the four directional demon kings sit outside the circle, and the thwarting angels for those kings sit within.

3. The Cosmos they Inhabit

This idea of going to “play” with a different cosmos can be hard to get your head round. After all, everyone thinks their worldview and idea of how things are in the cosmos is right, right? Relativism can be hard, especially when it comes to deeply held beliefs that are often also tied up in personal experience.

This idea of going to “play” with a different cosmos can be hard to get your head round. After all, everyone thinks their worldview and idea of how things are in the cosmos is right, right? Relativism can be hard, especially when it comes to deeply held beliefs that are often also tied up in personal experience.

Try imagining it like this – a huge endless space filled with countless temples. In and around each temple, the view of the cosmos inherent to the religion and gods/spirits of the temple not only holds sway but is reality. So if you’re going to go and interact with those gods/spirits, you need to “go to their temples”.

Naturally though, there are a lot of common threads between the “temples” and a *whole* lot of shared history. Lots of people (not to mention those dratted grimoires) did a lot of traveling, spreading ideas and magical tech like magical clap to everyone they came across. So some of those temples aren’t exactly autochthonous in what they display.

But that doesn’t mean that we can start engaging in fuckery like going to a Pagan “temple” where we feel more comfortable and essentially placing a collect call to a more Judeo-Christian “temple” where we might think some of the spirits are cool but not the head honcho. That’s kind of rude. Sort of like calling up someone you don’t know at an unsociable hour, and not only asking them to help you out but to do it entirely on your terms.

Some might even argue that they all really share the same basement too anyway, you know…if you go to the *right* sub-level. Even worse, there are some rumors that some of those grimoires even made it down to the basement a few centuries before the current crop of magic users started their sneaking expeditions down there. So you know, that’s a whole lot to take into consideration.

sub-level. Even worse, there are some rumors that some of those grimoires even made it down to the basement a few centuries before the current crop of magic users started their sneaking expeditions down there. So you know, that’s a whole lot to take into consideration.

But it’s also a lot of possibilities and scope for improvement. Because magic isn’t something that is static and relegated to what is passed down in books – they can only help us put our feet on the path. No, magic is a living thing that evolves in concert with our interactions with the Other (once we have gained our proper introductions, of course). That, to my mind, is the greatest thing of all about magic, and of course, it all starts with the circle.

Sources

Dr Stephen Skinner – Techniques of Graeco-Egyptian Magic

Jake Stratton-Kent – Geosophia: The Argo of Magic (Vol II)

In the first book of the Encyclopedia,

In the first book of the Encyclopedia, tradition. The PGM date from between 200 B.C.E and 500 C.E, and are the product of intense cross-cultural interaction and blending in the Mediterranean. Kadmus sums this up best when he writes in his review that the PGM are “just as much Egyptian Magical Papyri as Greek ones”.

tradition. The PGM date from between 200 B.C.E and 500 C.E, and are the product of intense cross-cultural interaction and blending in the Mediterranean. Kadmus sums this up best when he writes in his review that the PGM are “just as much Egyptian Magical Papyri as Greek ones”. without the benefit of reading the Encylopedia, I think that if there’s one thing the grimoires teach us, it’s that the world was never so simple. Cultures interacted, people traveled, aspects of the ‘not us’ found their way in to the ‘us’, and the world marched ever on. Traditions grew, metamorphosed, and sometimes even died. The Armadel method was transmitted, spirit lists persisted (

without the benefit of reading the Encylopedia, I think that if there’s one thing the grimoires teach us, it’s that the world was never so simple. Cultures interacted, people traveled, aspects of the ‘not us’ found their way in to the ‘us’, and the world marched ever on. Traditions grew, metamorphosed, and sometimes even died. The Armadel method was transmitted, spirit lists persisted (