Which Witch is Witch

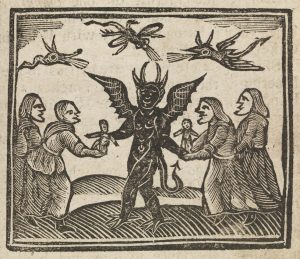

What is a witch, and who gets to call themselves one? If ever there were two more controversial or ire-provoking questions than these, I am yet to find them. Nowadays, those of us who live in the post-Industrial nations of the world treat the word “witch” as a title to claim and squabble over. Which is ironic really, when you consider that for many centuries, the witch was a person to fear, a bane on cattle and crops; and for those who were accused of being one, a path to prosecution and possibly either the gallows or pyre.

I’ve already blogged about the origins of the word “witch,” or more specifically, the first attestations of its Old English ancestor: wicce (f)/wicca (m)/wiccan (pl). As I argued then, given the contexts in which those attestations appear and their clear parallels in Old Norse narratives of Heathen magic and magical practitioners, the first Witches were most likely a kind of Heathen ritual or magical specialist.

Now, that’s all well and good. But what about practitioners today? After all, not everyone claiming or squabbling over the title of “witch” is a Heathen. If anything, most seem to consider Heathenry and Witchcraft two completely separate paths—paths that are, for the most part, largely in opposition to each other. Additionally, for many within the Traditional or Folkloric Witchcraft communities, the “real” witches were Christians, and it’s the Pagans and Heathens who are the latecomers to the Craft. (Another irony given those aforementioned origins!)

Perception and Meanings

So, with all that said, where do we go as modern practitioners? Because believe it or not, this isn’t about telling everyone they have to be Heathen or GTFO of the Craft!

The thing about words is that their meanings change over time. People have literally spent centuries altering the definition of witchcraft to fit their social, political, and religious agendas. “Witch” and “witchcraft,” simply put, were labels of exclusion used to delineate and enforce the boundaries of society while identifying those people, practices, and beliefs perceived to be harmful to that order to eradicate them (see Kieckhefer cha. 8 for further discussion). Given the central role of perception here—which is itself incredibly malleable and largely shaped by belief—it’s little wonder those definitions have shifted so much over the centuries. That perception of harm is why it was entirely possible for the same person to be considered a “cunning person” or “charmer” by some, and a “witch” by others. To quote Kirsteen Macpherson Bardell in her paper, Beyond Pendle: the ‘lost’ Lancashire Witches:

“Again, the evidence indicates that healers had a widespread reputation in the community but that this ambiguous connection with magic could turn into suspicion of something more malevolent.”

The witch who could heal could also hex, and all that. A precarious position for any practitioner.

Moreover (and to further complicate matters), “witch” has become the go-to gloss for any word used to describe ritual specialists in other cultures as well, its application largely dependent on how those practitioners were perceived by cultural outsiders. This not only expanded the definitions of “witch” even further, it also obscured, shifted, or even outright erased the original understandings those cultures had of those practitioners. (An accusation we can also lay at the feet of the appropriated version of the term “shamanism” as well, if we’re being honest.)

Either way, it’s little wonder we have so much to argue over now.

Unfortunately, the truth of the matter is that outside of its original cultural and religious context, the word “Witch” doesn’t really have a fixed meaning. Both now and in the past, it’s been used as a box of sorts. For some, that box was a place to toss the people and things they wanted to get rid of, while for others, that box holds something treasured to be gatekept. In one box, lives one kind of person’s nightmares, whereas the other box holds another kind of person’s ideals and dreams.

Again and again, it’s perception that shapes those walls.

The Familiar Thread

Nebulous though the meanings of “witch” can be, however, there is something more solid to be found in that cloud. A way to sort through the mist, if you will. As unlikely as it may seem, there is a core there that exists regardless of religious belief, socio-political goals, or mystical aspirations. We see this core in a theme that is repeated over and over from the eleventh century writings of the early English homilist Ælfric (and likely earlier) to the early modern English and Scottish trial accounts.

It’s the presence of “devils” or familiar spirits, be those familiar spirits Otherworldly or Dead. A thread that predates the development of the continental witchcraft narrative by centuries.

“Now some deceiver will state that witches (wiccan) often say truly how things will turn out. Now we will say truly that the invisible devil who flies around the world and sees many things makes known to the witch what she may say to men so that those who seek out that wizardry may be destroyed.”

From De Auguriis by Ælfric of Eynsham

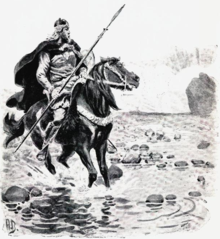

In my blog talking about those earliest attestations of wicce/wicca/wiccan, I discussed the strong parallel between King Alfred’s 9th century renegotiation of Exodus 22:18 and the image of the Old Norse seeress or völva in the Poetic Edda poem Völuspá. To summarize for those of you who are yet to read that post, both the wiccan of Alfred and the völva of the Edda were portrayed traveling between homes, exchanging magic and seership for the hospitality of their (predominantly female) hosts—a theme we see repeated a number of times in the Old Norse sources.

Given the common root of the early English and Norse cultures and their history of exchange and interaction, shared themes or patterns can hardly be surprising. Yet despite this long relationship, even the suggestion that early English witches might have been analogous to the Norse völur in some ways is still somewhat controversial.

Perhaps it hits too many of the same buttons indiscriminately smashed by Margaret Murray for comfort? Or maybe anti-Wiccan sentiment among modern Heathens is to blame? I suspect both may be a part of it. However, it’s also important to point out here that the völva (much like the shaman) isn’t nearly so tarnished by those centuries of negative PR. This is especially the case among Anglophones, but it likely extends into other cultures too given the outsized influence of Anglophone media on the rest of the world. In short, völva has a certain cachet that “witch” simply doesn’t have and perhaps offers a way to be “witchy” without inviting the same degree of hostility from others. Any comparison between the two then must feel like a sullying of something dearly held.

You see, even as Pagans and Heathens we are shaped by those Christian perceptions; some of us still borrow our prejudices instead of setting them aside.

Devils? Nah. Let’s Talk Elves and Witches!

However, to return to my point, that partnership between witches and so-called “devils” also appears in Old Norse sources. Over and over, we find female magical practitioners in league with other-than-human people.

For example, in Ynglinga saga, Freyja (a goddess associated with magic referred to as seiðr) is described as a blótgyðja or “sacrificial priestess” and appears to lead the cult centered around her brother’s burial mound. Her brother, of course, is Freyr, a god described as the ruler of Álfheimr or “Elf Home” (cognate to the Scots word Elfhame) in the poem Grímnismál. Another place we see this partnership between a “witch-coded” priestess and elf-coded male is in chapter 28 of Örvar-odds saga, where we find a king by the name of Álfr (literally “elf”) and his wife Gyðja (“priestess”), who appears connected to Freyr. Gyðja is also depicted shooting magical projectiles from her fingernails, an ability we also see demonstrated in Jómsvíkinga saga by the goddess Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr, who Hilda Ellis Davidson identifies with Freyja (Davidson, Roles of the Northern Goddess pp. 177-178).

And while we’re on the subject of magical projectiles (also known as “elfshot”), allow me to mention a couple more sources that feature this theme as additional illustrations of this partnership. The first source I want to mention is the 10th century metrical charm Wið Færstice (“Against a Stitch”), which features a narrative set at a burial mound that likely describes witches shooting projectiles made by elven smiths. The second source I want to mention is the confession of the 17th century witch, Isobel Gowdie, in which she claimed to obtain her magical projectiles from elves (and the Devil), who made their houses in mounds (Alaric Hall, Elves in Anglo-Saxon England pp. 112-115).

Despite the centuries between them, the narrative of Wið Færstice and themes of Isobel Gowdie’s confession align in that both involve witches shooting elf-made magical projectiles and mounds. Quite remarkable when you think about it! Clearly, those things go together like PB&J!

(Can confirm.)

I could go on (no really, I could; this is my special interest). I’ll spare you all for now, though. We’ll be here all day otherwise.

Moving Forward

The partnership between witch and familiar is perhaps one of the oldest and most consistent threads of the witchcraft story regardless of era, at least as it has played out among English and Scots-speaking groups in mainland Britain, or in other words: those groups who once would have likely used the words wicce/wicca/wiccan in their daily speech. While this pattern can also be seen in other cultural groups within the British and Irish Isles as well as continental witchcraft narratives, those are beyond the scope of this post.

Now does that mean that everyone has to have a familiar spirit in order to be a “real” witch?

Not necessarily. What I will say, however, is that one does have to be somewhat other. Some of us come by that otherness via ancestry i.e. someone way back when made some connections that subtly changed them and those who came after them, while some of us become other through encounters with the Dead and/or Otherworldly, eventually founding relationships. It may not be popular to say this, but that’s the thread.

Some Personal Theorizing

My personal theory is that the witch originally began as an analog of the Old Norse gyðja, who, as Terry Gunnell points out in his paper Blótgyðjur, Goðar, Mimi, Incest, and Wagons: Oral Memories of the Religion(s) of the Vanir, was mostly associated with the cult of Freyr in the sources. This interpretation would accord well with the etymology put forth by the linguist Guus Kroonen, which traces the word’s derivation from the same linguistic roots as the Proto-Germanic *wiha-1 and *wiha-2 (“holy” and “sanctuary”). A second etymology that also accords well with this interpretation considering the centrality of burial mounds in some of these narratives is that given by the American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots, which traces wicce/wicca to the Germanic *wikkjaz or “necromancer.” An association that also appears in the later Aldhelm glosses as well.

For tonight, god is an (elf) DJ.”

Final Words

Still, that thread doesn’t erase those centuries of loose meanings and adaptations. If the word “witch” inspires you, then I encourage you to respectfully take on that mantle. I am not here to police or gatekeep you or your practice. That’s just tiring and pointless. As I’ve said before (many times), the Craft protects itself. Just know that the witch-mantle is weighty and can get you into trouble. Be mindful of its history, both the good and the bad, and remember on whose side you stand.

And whatever you do, never, ever forget the possibility that it all began with devotion and service.

Now, wear that mantle accordingly.

Sources

Davidson, Hilda E., and Hilda R. Davidson. Roles of the Northern Goddess. London: Psychology Press, 1998.

Hall, Alaric. Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity. 2007.

HarperCollins Publishers. “Appendix I – Indo-European Roots.” American Heritage Dictionary – Search. Accessed May 9, 2025. https://ahdictionary.com/word/indoeurop.html.

Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Kroonen, Guus. Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill Academic Publishers, 2013.

Poole, Robert, and Kirsteen Macpherson Bardell. “Beyond Pendle: the ‘lost’ Lancashire Witches.” In The Lancashire Witches: Histories and Stories. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Seven Viking Romances. London: Penguin UK, 2005.

Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010.

Terry Gunnell. “Blótgyðjur, Goðar, Mimi, Incest, and Wagons: Oral Memories of the Religion(s) of the Vanir.” The Center for Hellenic Studies. Last modified March 30, 2021. https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/part-ii-local-and-neighboring-traditionsterry-gunnell-blotgydjur-godar-mimi-incest-and-wagons-oral-memories-of-the-religions-of-the-vanir/.

“Örvar-Odds Saga.” Snerpa.is / Heim. Accessed May 9, 2025. https://www.snerpa.is/net/forn/orvar.htm

figure. Unsurprisingly, he’s been interpreted as a representation of Freyr. But for all of his blessings beneath the belt, this ‘God of the World’ is all of 7cm/2.75” tall. So, pocket-sized for your convenience. Just ask Ingimund from the Vatnsdæla saga about his missing Freyr amulet..

figure. Unsurprisingly, he’s been interpreted as a representation of Freyr. But for all of his blessings beneath the belt, this ‘God of the World’ is all of 7cm/2.75” tall. So, pocket-sized for your convenience. Just ask Ingimund from the Vatnsdæla saga about his missing Freyr amulet..

6.7cm/2.6” (with his hammer taking up a good deal of those centimeters/inches).

6.7cm/2.6” (with his hammer taking up a good deal of those centimeters/inches).

I walk. I hear the rush of the water and feel the wind beating against my ears.

I walk. I hear the rush of the water and feel the wind beating against my ears. Christian alike.

Christian alike. practices like that though, if I’m being honest.)

practices like that though, if I’m being honest.) in my heart even, and search them out with my eyes.

in my heart even, and search them out with my eyes. too.

too. oppression or seeking the ruination of human souls. There wasn’t even anything even vaguely chthonic about this ‘demon’ either, and the only bowels involved were the bowels that live inside my body.

oppression or seeking the ruination of human souls. There wasn’t even anything even vaguely chthonic about this ‘demon’ either, and the only bowels involved were the bowels that live inside my body.

one talks about the labor of birthing the next generation, the countless hours spent clothing families and producing textiles to sell, or how it was the work of women that created the sails that drove the ships and

one talks about the labor of birthing the next generation, the countless hours spent clothing families and producing textiles to sell, or how it was the work of women that created the sails that drove the ships and

entice you into some kind of oath, your first move is always research. Go find out everything you can about them, and if it’s not available in physical sources, go pester allies for more information. Because there are a whole bunch of things you need to know here. For example, you need to know their MO; if they’re presenting themselves as they actually are; how others have fared dealing with them; and if they have a GSOH and enjoy long walks on the beach at sunset. Because all of that will not only help you figure out *who* you’re dealing with, but also help you better word any oaths you make so that you can do stuff like insert more protective clauses (which is #winning, trust me).

entice you into some kind of oath, your first move is always research. Go find out everything you can about them, and if it’s not available in physical sources, go pester allies for more information. Because there are a whole bunch of things you need to know here. For example, you need to know their MO; if they’re presenting themselves as they actually are; how others have fared dealing with them; and if they have a GSOH and enjoy long walks on the beach at sunset. Because all of that will not only help you figure out *who* you’re dealing with, but also help you better word any oaths you make so that you can do stuff like insert more protective clauses (which is #winning, trust me).