An Encounter with the Restless Dead

The saga refers to what happened as wonders, but I would not call them such. After all, people had died. Oh, it wasn’t just those who had initially died. No, they had returned, others had fallen sick, and more had joined their ranks.

Unlike the dead of other Indo-European descendant cultures, the dead always walked in Iceland. Draugar, they were called, revenants. Other places had them too – the Greeks, for example. They too knew revenants and practiced arm-pitting dead enemies, severing the vital tendons that would allow ambulation should the deceased arise to walk and seek revenge (Ogden 162). But the Greeks also had ghosts; the preference for cremation during the Archaic Era coincided with a diversification of Greek underworld beliefs. The previously faceless dead that existed unaware of the living world above now understood that their descendants poured out and burned offerings for them. The expansion of cremation burial also coincided with the arrival of the psychopomps – a role which would be extended during the Classical Era (F. P. Retief “Burial Customs”).

The Icelanders though, they did not burn their dead, and so their dead walked as you or I do (Davidson 9).

The Court is Convened

But these were not the mindless rotting zombies of movies; let’s not think that they were. No, draugar didn’t rot, and were fully capable of thought and action, passing through the earth of their mounds to visit and all too often harass the  living. But their visits also brought sickness, and that’s just what they brought to the people of a place called Frodis-water.

living. But their visits also brought sickness, and that’s just what they brought to the people of a place called Frodis-water.

So the people of Frodis-water decided to hold a dyradómr, a kind of door-court during which the dead would be judged in accordance with the law, and hopefully sent on their way. Now doorways are significant; they’re liminal places where living and dead can meet. To keep your beloved dead close, you might bury them in a doorway, and the door post holes found before Bronze Age burials could not have been a coincidence (Hem-Eriksen “Doorways”). So they held their door-court at the doorway and called the dead to them to hear their judgement.

Surprisingly, the dead took their judgements and left without argument. But that was the power of the law, and no one living or dead, wants to reside outside of the protection of the law.

The Law is Sacred

You see, law – or at least a certain kind of law – was sacred. It was the difference between order and chaos, between thriving and destruction, and as such, it was valued. It is the ŗta of the Vedic texts and the asha known to the Zoroastrians. These were in turn cognate with the Greek aristos, ‘the best’; harmonia, ‘harmony’; and ararisko, or ‘to fit, adapt, harmonize’. All though, can probably be traced to the same Proto-Indo-European root word, *H²er-, or ‘to fit together according to the proper pattern’ (Serith 30).

The First Rule?

We don’t know that “proper pattern” though, and we cannot claim to know it despite the fact that it would be useful to anyone who follows any traditions inspired by pre-Christian IE cultures. However, we can perhaps infer what  some of those laws might be. I am going to infer one right now: that our rights to this world are lost when we breathe our last.

some of those laws might be. I am going to infer one right now: that our rights to this world are lost when we breathe our last.

This is why the dead must be dragged by fetters or snares from the world of the living. It is why the Rig Veda refers to the “foot fetter of Yama” (the Lord of the Dead); why there are hel ropes in the Sólarljóð; why Horace wrote of mortis laqueis, or “snares of death; and it is why Clytemnestra had a net (Giannakis “Fate-As-Spinner”). The dead do not wish to go, so they must be dragged. It is noteworthy that they only return at the end of all things (Ragnarök), or that their return brings sickness and death. This is one law we can infer; this is part of the proper pattern.

The Rule of Law

Another is that nothing exists outside of this. To be removed to the Underworld is not to be removed from the reach of law. The Underworlds are varied, and descendants would not have made ancestor offerings were those ancestors truly gone and wholly disconnected. We must always remember that a human community has two sides: the living who dwell in the Middle Earth, and the dead who dwell below.

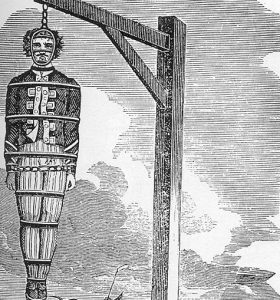

The story of the door-courts suggests that both living and dead are equally bound by the law. We also see this reflected in the burial customs of those deemed to exist outside the protection of the law. These were often the criminals left to rot at the crossroads, those buried in unhallowed grounds, and those who were too young at the time of their passing to be formally accepted in a community (Petreman “Preturnatural Usage”). Is it any coincidence that the materia magica sought from the human body came most often from these sources? Is it also coincidence that those were the sources thought by the Ancient Greeks to carry the least miasma (Retief “Burial”)? To exist as dead inside the protection of the law is to sleep soundly – or at least it should mean that. Of course, there have always been violations as Burke and Hare could well attest.

The story of the door-courts suggests that both living and dead are equally bound by the law. We also see this reflected in the burial customs of those deemed to exist outside the protection of the law. These were often the criminals left to rot at the crossroads, those buried in unhallowed grounds, and those who were too young at the time of their passing to be formally accepted in a community (Petreman “Preturnatural Usage”). Is it any coincidence that the materia magica sought from the human body came most often from these sources? Is it also coincidence that those were the sources thought by the Ancient Greeks to carry the least miasma (Retief “Burial”)? To exist as dead inside the protection of the law is to sleep soundly – or at least it should mean that. Of course, there have always been violations as Burke and Hare could well attest.

From these perspectives, the case against the dead at Frodis-water may already seem airtight. After all, we’ve already established that by virtue of being dead they’re not supposed to be in the world of the living, and that they are just as subject to this “proper pattern” law as we ourselves are. However, there is one more legal argument pertinent to the dead that we have not yet examined, and that is the law of possession.

Claiming and Keeping Space

Fire has always been sacred to the various Indo-European descendant cultures, and was considered to have various functions. We’re perhaps the most familiar with fire as a medium through which offerings may be made to  the holy powers, but fire also played an important role in property ownership too. For the Norse, carrying fire sunwise around land you wished to own was one method of claiming that land (LeCouteux 89), and under Vedic law new territory was legally incorporated through the construction of a hearth. This was a temporary form of possession too, with that possession being entirely dependent on the ability or willingness of the residents to maintain the hearthfire. For example, evidence from the Romanian Celts suggests that the voluntary abandonment of a place was also accompanied by the deliberate deconstruction of the hearth. And the Roman state conflated the fidelity of the Vestal Virgins to their fire tending duties with the ability of the Roman state to maintain its sovereignty. The concept of hearth as center of the home and sign of property ownership continued into later Welsh laws too; a squatter only gained property rights in a place when a fire had burned on his hearth and smoke come from the chimney (Serith 2007, 71).

the holy powers, but fire also played an important role in property ownership too. For the Norse, carrying fire sunwise around land you wished to own was one method of claiming that land (LeCouteux 89), and under Vedic law new territory was legally incorporated through the construction of a hearth. This was a temporary form of possession too, with that possession being entirely dependent on the ability or willingness of the residents to maintain the hearthfire. For example, evidence from the Romanian Celts suggests that the voluntary abandonment of a place was also accompanied by the deliberate deconstruction of the hearth. And the Roman state conflated the fidelity of the Vestal Virgins to their fire tending duties with the ability of the Roman state to maintain its sovereignty. The concept of hearth as center of the home and sign of property ownership continued into later Welsh laws too; a squatter only gained property rights in a place when a fire had burned on his hearth and smoke come from the chimney (Serith 2007, 71).

Sovereignty and the Dead

There is more here too – the matter of sovereignty looms large. So too perhaps is a form of imitation of the relationship between king and goddess of sovereignty played out here between men and the wives who keep the hearth fires burning. To maintain the hearth was to maintain possession of property, and to maintain the hearth, a woman was required. (Or several, if you happen to be the Roman state.)

fires burning. To maintain the hearth was to maintain possession of property, and to maintain the hearth, a woman was required. (Or several, if you happen to be the Roman state.)

And here is where I come to my final argument regarding law and the dead: the dead keep no fires in the habitations of the living. Without the ability to maintain a hearth fire, the dead cannot claim sovereignty in the land of the living, and this is an important point to bear in mind. Because while we often joke that possession is nine tenths of the law, thankfully for the people of Frodis-water, it most likely was that which saved them.

Sources

Davidson, H. R, Ellis. The Road to Hel: A Study of the Conception of the Dead in Old Norse Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013. Print.

Giannakis, George. “The “Fate-as-Spinner” Motif: A Study on the Poetic and Metaphorical Language of Ancient Greek and Indo-European (Part II).” Indogermanische Forschungen Zeitschrift Für Indogermanistik Und Historische Sprachwissenschaft / Journal of Indo-European Studies and Historical Linguistics 104 (2010): 95-109. Web.

Hem Eriksen, Marianne. “Doorways to the Dead. The Power of Doorways and Thresholds in Viking Age Scandinavia.” Archaeological Dialogues 20.2 (2013): 187-214. Web. 31 Mar. 2017. <https://mariannehemeriksen.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/eriksen-marianne-hem-2013.pdf>.

Lecouteux, Claude. Demons and Spirits of the Land – Ancestral Lore and Practices. Inner Traditions Bear And Comp, 2015.

Ogden, Daniel. Magic, Witchcraft and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Petreman, Cheryl. “Preternatural Usage of Human Body Parts in Late Medieval and Early Modern

Germany.” Diss. U of New Brunswick, 2013.

Retief, Fp, and L. Cilliers. “Burial Customs, the Afterlife and the Pollution of Death in Ancient Greece.” Acta Theologica 26.2 (2010): n. pag. Web.

Serith, Ceisiwr. Deep Ancestors: Practicing the Religion of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. ADF Pub., 2009.