Within the past two days, I’ve had two friends tell me of sleep disturbances that had a certain quality of otherness about them. One person had the experience while we were camping in the Black Hills of Maryland, and the other in her own home. In the case of the first person, she’d felt physically touched by whatever it was through the wall of her tent – a touch that she felt was a very deliberate poke which had been kind of ‘introduced’ in her dream before it happened. In the case of the second person, it was more of a classic ‘Old Hag’ experience that they had had to fight off.

To Me Came A Dream

In both cases, each individual felt very strongly as though what had happened wasn’t just a simple nightmare, and that some kind of interaction with the Other had taken place. It’s very easy for modern people to discredit dream and what happens in the altered states of consciousness between sleeping and awake.

However, as I have discussed previously in this blog, this attitude towards dream seems to have been the result of a concerted effort by Christian authorities to dismantle the power of dream among their flocks in order to censor dream, for to censor dream is to censor one form of access to the Otherworld. In Germanic tradition, dreams were thought of as coming from outside the sleeper – a concept that is reflected linguistically in both Old Norse and Old English in phrases such as dreymdi mik draumr (“a dream came to me”) and mec gemætte (“to me came a dream”) (Pollington 490). The ON term draumstolinn suggests that the ability to dream was one that could be stolen, and in The Saga of the Jómsborg Vikings a man is refused marriage if he does not dream (LeCouteux 28).

However, the sleeper was not entirely passive, and as we shall see, could sometimes also enact their own visitations in dream.

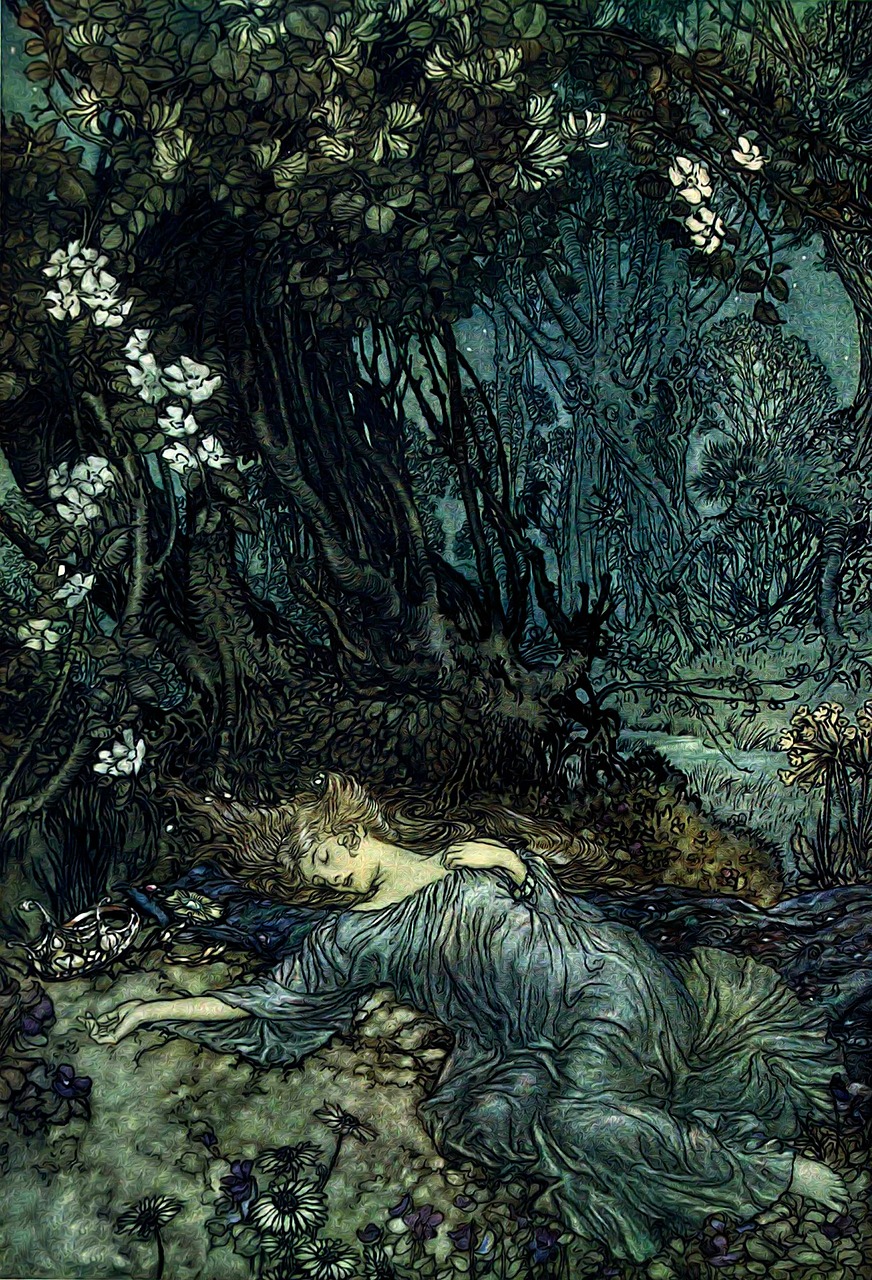

So dream was important. It wasn’t just some whimsical and harmless thing to the Pagan/Heathen mind, but a way in which the sleeper could interact with both the Otherworld, and other sleepers. And it was consideration of my friends’ dreams that got me thinking about the bad side of dream: maran, night-walkers, and elves.

”Wið eallum f?ondes costungum”

When it comes to discussing maran, night-walkers, and elves, it can be hard to give solid definitions. Mare (from which we derive the word “nightmare”) could refer to either a human woman – usually but not always intentionally a witch – that attacked sleepers, or a supernatural being that did the same (Jolley 86, Hall 125). The term night-walkers seems self-explanatory, though Hall still expresses uncertainty as to what they could have been in more precise terms (Hall 124). And the problems of defining what an elf was considered to be (not to mention their relationship to magic and witches) are perennial.

What we can say with some certainty though, is that certain effects were considered to be common to these beings, and that they were connected/overlapped in terms of function. In some charms, we may see this uncertainty as to who/what was doing what to the patient, reflected in the more general terms f?ondes costunga (“tribulations of the enemy”), and/or Ælfs?den (“elf-seiðr” – a form of magic) used.

On the symptoms of attack and forms of treatment however, the OE magico-medical sources are remarkably consistent on the matter of nightmares, and it is upon these consistencies that I shall now focus.

Symptoms of Attack

For those of you who have experienced the terror of “sleep paralysis” (or as it’s sometimes called, “Old Hag”), this is all going to sound very familiar. While the explanation for this sleep disturbance has changed in modern times (no  elves or night-goers need apply!), modern descriptions of this experience would have been familiar to our ancestors. In some accounts, such as that of the Swedish king Vanlandi of the Ynglinga saga, the victim was even “trod on” or “pressed down on” until dead. It is worth mentioning here that the attacking force was the witch/mara Drifa (Hall 125, 135). Interestingly, while the Ynglinga saga was composed post-conversion, a segment of the 9th century Ynglingatal referencing the death of king Vanlandi as a result of the witch (referred to in the Ynglingatal segment as mara) attests to the potential Heathen origins of this concept.

elves or night-goers need apply!), modern descriptions of this experience would have been familiar to our ancestors. In some accounts, such as that of the Swedish king Vanlandi of the Ynglinga saga, the victim was even “trod on” or “pressed down on” until dead. It is worth mentioning here that the attacking force was the witch/mara Drifa (Hall 125, 135). Interestingly, while the Ynglinga saga was composed post-conversion, a segment of the 9th century Ynglingatal referencing the death of king Vanlandi as a result of the witch (referred to in the Ynglingatal segment as mara) attests to the potential Heathen origins of this concept.

Rather disturbingly, there was also potentially considered to be a sexual or lustful element to these nocturnal attacks too. As Hall points out, mære was glossed with incuba in the 7th century (Hall 125). This connection is repeated in the 13th century South English Legendary which not only juxtaposes maren with eluene (or “elves”), but describes these attacks in sexual terms (Hall 140-142). This sexual aspect is also alluded to by Karen Jolly in Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context” (Jolly 149).

Other symptoms of attack by maran, night-walkers, or elves that can potentially be discerned from the sources are those of fever and delusion (Hall 121-125). Though it bears pointing out here that fevers often come with delusion, it is also worth noting that there is an entire category of elf-related illnesses in the OE magico-medical texts (Hall 96-108). In any case, whether (more specifically in this case) the elves are considered to cause the sickness or the more delusional symptoms associated with fever, Hall seems to imply that the sick are potentially more of a target by virtue of being sick:

Ælfs?den is also associated with nihtgengan and with the riding of the sick by maran.”

(Hall 130)

Lastly, before finishing this current section, I would like to point out the parallels between the ON and OE lore regarding maran/night-walkers, and that of the Hmong being, the Dab Tsog.

In the late 70s to mid 80s, Hmong refugees became something of a curiosity to US medical professionals and researchers for one reason and one reason only: their men were dying in their sleep. There was no explanation that could be found, and the term SUNDS (or Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome) was coined by the FCDC.

However, the cause of death was no mystery to the Hmong themselves – it was the Dab Tsog who brought the chest crushing death of the Tsog Tsaum. Incredibly there are survivors of SUNDS, who when interviewed, related horrifying dream-experiences in which they were attacked by a kind of creature that tried to kill them by sitting on their chests and forcing the air out. These survivors also experienced paralysis and remembered being able to clearly hear the sounds of their houses around them.

Sound familiar?

The Hmong are not the only people to report these kind of beings either, the Dab Tsog mirrors cases attributed to the Filipino Batibat.

But now we have faced the terrors, how do we keep the terrors far from our own beds and dreams?

Sources

Alaric Hall – Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender

and Identity

Karen Jolly – Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context

Claude LeCouteux – Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral

Doubles in the Middle Ages

Stephen Pollington – Leechcraft: Early English Charms, Plant-Lore and Healing