The Wolf in a Tower Time Oracle

Like many mornings during this period of time many call Tower Time, I woke up to a message from a friend about “weird shit.” My friend was asking me if I’d seen John Beckett’s most recent blog post. You may have already seen it as it’s doing the rounds. But in case you haven’t, it’s about an oracular ritual during the Mystic South conference and the messages received by some of the participants.

I’m going to be honest here: None of these messages are particularly surprising to me. If anything, much of it tallies with what I’ve been getting from other sources.

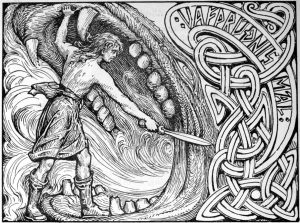

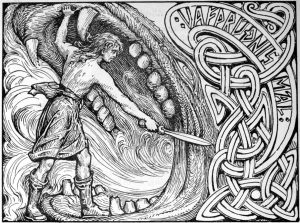

But there’s one message in particular that I want to focus on today. It’s the message that there must be joy or “Fenris will eat the world.”

Wolves and Greed

On the surface, Bergrune’s message (an oracle I know personally) may sound simplistic and strange. But I’ve found myself turning it over and over in my mind. This past weekend I taught the second in a two-part series of classes about Animistic Heathenry and magic in which greed was a major talking point. This message dovetails nicely with my current meditations on how best to deal with greed.

In her book The Seed of Yggdrasill, Maria Kvilhaug points out that wolves are associated with greed in the ON sources. This is something Snorri is quite clear on in Skáldskaparmál, the text in which he teaches the art of writing and understanding the language of poetry.

“But these things have now to be told to young poets who desire to learn the language of poetry and to furnish themselves with a wide vocabulary using traditional terms; or else they desire to be able to understand what is expressed obscurely.”

Sturluson, Snorri. Skáldskaparmál (Faulkes trans.). p. 64.

Those of you who are already familiar with Norse mythology will probably already know the names of Óðins wolves: Geri and Freki. Both names are words that mean “greed,” and both names can be used as common nouns for “wolf” in skaldic poetry (Sturluson. 135, 164). Along similar lines, it was also considered normal to refer to wolves in relation to blood and corpses as their food and drink (Sturluson 135).

The Meanings in the Myth

From Maria Kvilhaug’s perspective (which I share), the ON myths are not simply stories of gods and other beings. They contain true wisdom if you know how to look for it. Kvilhaug is someone who’s learned how to look for it. And if we listen to her, we can learn to look for it too.

Bergrune’s message mentioned Fenrir, which inescapably leads us to the Ragnarök myth – an appropriate choice in our collapsing world.

So, what wisdom can we find in the myth of Ragnarök? What lesson can we take from this?

As a wolf, Fenrir may be thought to represent greed, and greed brings destruction. His opponent at Ragnarök is

Óðinn, the giver of our breath-soul. We should ask ourselves here about the possible meanings of the god who gave breath-souls to humans falling to greed.

To me, the battle between this soul-giving deity – one of our creators even – and greed indicates that this isn’t only a battle for gods. It is a battle that we humans face too.

The Nature of Greed

There are surprisingly few psychological studies about the causes of greed. But what I managed to dig up seems to suggest that greed often has its roots in feelings of lack, unmet physical/emotional needs, and anxiety about future struggles.

But what about countering greed? Here is where we can perhaps take wisdom from another myth of Fenrir.

Binding the Wolf

In Gylfaginning, the gods read prophecies predicting destruction by Loki’s children and decide to act. Snorri tells us they cast Hel into Niflheim and Jörmungandr into the ocean. With Fenrir though, they brought him home and raised him in their halls. But as he grew bigger, they became increasingly afraid and decided to try binding Fenrir with chains.

Here is where my personal conclusions diverge from Kvilhaug’s. This is only to be expected; a myth can be read from multiple perspectives and hold more than one truth.

The first chain is Læðing, which Kvilhaug translates as “Harm Council” (Kvilhaug 442). She also provides a second possible translation, but I’ll refrain from providing that here as it diverges from the points I want to make.

This idea of a chain called “Harm Council” reminds me of the kind of measures many attempt to overcome negative qualities. You’re probably already familiar with the kind of measures I mean. Everything from cruel self-talk, strict self-discipline (then more self-talk when it fails), and in extreme cases mortifying the flesh. In a sense, when we put it this way, it’s not hard to see those measures as a “council of harms.”

This will probably come as no surprise to anyone who’s ever dealt with addiction. But it doesn’t take long for Fenrir to break that chain.

The second chain is Drómi, which means “Fetters.” An important point Kvilhaug makes is that “fetters” is a common metaphor for the gods themselves in Skaldic poetry. When viewed through this lens, I’m reminded of people who cling to religion and the imagined wrath of a deity as a way to keep themselves in line. To force themselves into what they see as better, more virtuous behaviors.

This lasts longer. But in the end, Fenrir breaks that too.

Binding the Wolf and the River of Hope

The final chain was, Gleipnir, or “Open One,” a silk-like binding that they used to bind the wolf to a giant stone slab on an island. At first glance, this is reminiscent of an oubliette. This island is not only a place to bind a potential future danger, but to forget about it as well. But we’re not yet done here, because Fenrir reacted violently and tried to bite them. From his perspective, this was likely a grave betrayal; after all, they were his foster family, and that meant a lot back then.

In response to his lashing out, the gods stabbed him through the roof of his mouth with a sword. A clear foreshadowing of the final doom he would meet at Viðarr’s hand. Then, they left him howling in pain and drooling. We’re told his saliva forms a river called “Hope” (Sturluson. 29).

As always, hope is often the only thing to continue flowing when we’re otherwise trapped and/or in pain.

Of course, those bindings didn’t work either in the long run. If anything, I’d argue those actions only made everything worse. As with all prophecies, you run the risk of fulfilling them yourself if you’re not careful – something that becomes especially likely the more afraid you are.

There’s a lot to take from this myth, a lot to notice about our society. Like the gods, we prefer the wolf bound in a place where we can forget about it or pretend it doesn’t exist. Kvilhaug translates the name of the waters surrounding the island (Ámsvartnir) as “Deep Darkener,” which for me at least, suggests a kind of oblivion (Kvilhaug 441). How many people even engage with the notion that greed is a serious and dangerous problem? That the act of non-stop consumption at the root of so many of our modern problems is something we need to reckon with before we bring about our own Ragnarök?

But What of Joy?

The message that Bergrune relayed, that message to embrace joy as a way of countering the “greed-wolf” seems simple on the surface. But here we need to ask ourselves how possible it is to feel real joy when you have unmet needs/a sense of lack/anxieties about the future that are so great they’ve collectively created a hole within your self and souls? A hole that seems bottomless and spurs an insatiable hunger to fill.

Here is where I believe the advice given via other oracular messages comes in.

These messages encourage us to interrogate those shadowy areas of self and souls. The advice to seek out those holes within us that gape like the maw of a wolf and try to understand them is excellent. It is also I believe, our way forward.

Because if we are to experience joy, real joy, then we need to first sit with our own greed-wolves and get to know them. As the myth of binding Fenrir hopefully demonstrates, we can’t bind them or pretend they don’t exist. Would not the wiser path be to figure out what drives them – the hurts in the holes and what they really want?

The wolf within isn’t inherently bad, just very good at what they do. They’re hunters at heart, and in turn directed by the heart and its ever-changing sea of emotions and hurts in their efforts. Again, they’re not inherently bad. I would argue these “wolves” are a part of self – a soul even. If you follow

Winifred Hodge-Rose’s Soul Lore work, this would be the hugr-soul.But who could these “wolves” be when cared for and those anxieties removed?

Domesticating the Wolf

Over the millennia, they’ve helped us to get food and stay safe. They’ve been our companions, workers, family members, protectors, and friends. Those wolves contributed immeasurably to the success of our species and eventually became dogs.

If you live with dogs and they’re anything like my little old man, you’ll know they show their love, pleasure, and joy in the most uninhibited and lovely ways. As a kid, my parents impressed upon me the importance of always raising dogs with love, kindness, and care; outside of genetic issues, the problems usually come when you raise them without those things. But when raised with love, care, and their needs (physical, yes, but more than that, the need for pack and to belong) provided for, they become life-long companions and true friends.

And this, I think, is where we find the key to our question.

A Life’s Work

In a sense, I believe we’re each born with a canine. But whether we end our lives with a canine that becomes a greed-wolf, a domesticated wolf, or even a dog is largely up to us. I see the process of getting to know that canine and taming them as part of the work of a well-lived life. It’s a challenge on the path to wisdom, a peril to the wise, and part of how we find victory in our own personal Ragnarök. The message was to “fight” the wolf with joy. But without first getting to know the “wolves” in our hearts, without that attention, love, and care – without healing the hurts of those holes – that joy will be hard to come by.

Food for thought, no?

I remember running wild under those steely grey skies, I remember countless adventures up on the moors and in the hidden places where adults didn’t seem to go: like the ‘ravine’ that was really a small stream down the side of an old Victorian factory that led into a more modern industrial park; or the ruins of Victorian farms built in the shadow of a brooding moor.

I remember running wild under those steely grey skies, I remember countless adventures up on the moors and in the hidden places where adults didn’t seem to go: like the ‘ravine’ that was really a small stream down the side of an old Victorian factory that led into a more modern industrial park; or the ruins of Victorian farms built in the shadow of a brooding moor. yourself nodding, and mentally giving the author a “Right on, man! You tell em!”? Well, I’m reading a book like that right now. Had this been a church sermon, the entire section that inspired this post would have had me shouting “Hallelujah” and “Praise the Lard!”, because it is just so nice to come across someone who writes things that you so completely agree with. That doesn’t happen a lot for me.

yourself nodding, and mentally giving the author a “Right on, man! You tell em!”? Well, I’m reading a book like that right now. Had this been a church sermon, the entire section that inspired this post would have had me shouting “Hallelujah” and “Praise the Lard!”, because it is just so nice to come across someone who writes things that you so completely agree with. That doesn’t happen a lot for me.