In my last post, I talked about the origins of modern rune magic and the importance of the stories we connect with when working magic. In this post, I’m going to talk about my modern rune magic practice and some of the ways in which I use rune magic in my everyday life.

My Introduction to the Runes

As ridiculous as it may sound, my first exposure to the runes was in primary

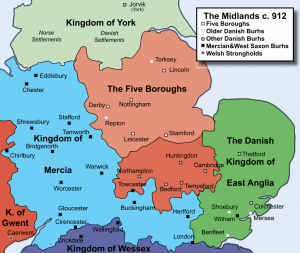

school at around the age of eleven. Back then our history classes focused on an era per school term, so we spent an entire term learning about the Vikings. Growing up in what was once the Danelaw, the history felt more immediate. I think it’s always nice to know about where you live, to talk about historical things happening in familiar places. And it was in these classes that we also learned about the runes.

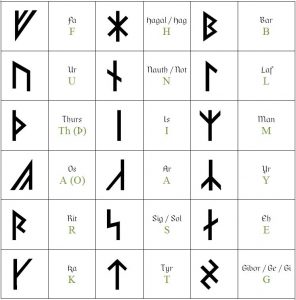

One of the things our teacher had us do during one of these classes, was to write a short essay in runes. We began with the Elder Futhark (with a few Anglo-Jutish additions to make transcription easier for us), but that was the start of it for me. It wasn’t long after that that I started to write on things in runes. I liked knowing a different alphabet and found them easy to write with and remember.

But it would be a while yet before I began to use them magically.

First Forays into Rune-ing It

My oldest magical journal goes back to 1998, and it’s here that I find the first references of rune magic in my practice. I was in my late teens back then, and on the whole, the Heathenry of those times was a lot less informed than the Heathenry of now. I was living in a backwards town that wouldn’t see its first coffee shop for another seven years, and my involvement in reconstructionism was just under a decade away. Despite being largely ignorant of the actual scholarship though (and absorbing a whole lot of dross),

I was deliriously happy soaking it all up anyway.

For those of you who weren’t around during this time, you have to understand how hard it was to find any information about Heathenry and/or magic at all in those days- especially if you grew up in a more rural area. And even when the internet became more widely accessible, it really wasn’t like how it is now. I mean, I’m talking about the days before Google existed here. So almost any source I could get my hands on was precious – even the junk. Printer access was also limited for me back then, and much of what I did find on websites and in library books had to be copied by hand.

But despite the lack of information, my rune divinations (which I performed using a set of runes I’d made out of oven-hardening clay), were shockingly accurate. I also started incorporating runes into what I would now recognize as petition papers and other forms of pen and paper magic. I used them to write charms and deity names when making offerings; visualized them and chanted their names; used them in shielding and protection, and for clearing spaces of unwanted guests; and enchanted with them to get work and escape bad situations.

If anything, I owe the life I have now to a combination of rune magic and fiber magic. And while my life isn’t perfect, it is measurably better than it was before. Embroidered rune magic put me on the path to the life I have now.

Early Stories

So as you might expect, I’ve done a lot of thinking about runes and how they work over the years.

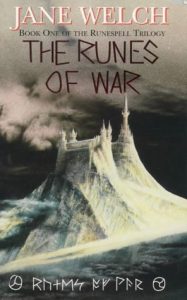

The first stories I told myself about the runes and how they work were that the runes themselves were inherently magical. That there was something in the shape and sound of the rune that made things happen. And why wouldn’t I think that when there are so many proponents of that idea out there? Moreover, I’ve also always been a fan of fantasy books and movies – a genre which largely reinforces that idea of runes. When you get down to it though, this isn’t all that different from the ideas put forth by Marby and Kummer; that these letters are not just letters that you can write words with, but energy fields permeating the cosmos that can be tapped into. (Like I said in my previous post, their ideas are still very pervasive.)

Runes and Story: The Mythology I Connect With

So which “rune stories” do I connect with now? Well, there are a few layers to this.

On the mythological level, I connect with the story of a One-Eyed god who gave all humans breath hanging on the tree for nine nights in a quest to snatch up the runes from (probably) Hel. I also (and this is perhaps more relevant to

magic), connect with the story of how the Nornir inscribe the ørlög of every person on a slip and speak it into being before (presumably) dropping it into Urðarbrunnr to rest together with all the other slips of ørlög in the waters. And sure, we don’t know that the Nornir write on those slips in runes, but there’s something about it that fits.

The magical use of runes in the way that we use them now may not be historical, but that’s not to say that we can’t connect them with older stories anyway. There is value to emulating the divine in ritual and magic. As the Taittirya Brahmana says, ” Thus the gods did; thus men do”.

Nowadays I find myself thinking about the story or stories attached to the runes quite a lot. I’ve written a little about the magical qualities of story in this blog before. (You can find this in my posts on the Hellier phenomenon and the intersection of that story with that in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina). Stories for me are inherently magical, and the more people buy into them, internalize and work with them, the more powerful that magic will be. And stories have never been more powerful; we now live in a world in which more people than ever before have access to books and mass media.

Runes and Story: The Rune Poems

On another level, the rune stories are the “stories” you find in the various rune poems. It’s possibly a stretch to call the short stanzas ascribed to each rune a “story” – they’re more like strange writing prompts if anything. But I’ve found they’re enough to spark the beginnings of story within the mind, stories that become enriched and filled out through time and experience.

The rune poems themselves have been theorized to have been created as mnemonic devices for the runes. But in some ways, I use the runes as mnemonic devices for the small “stories” of the poems. When I chant, visualize, create bindrunes, or stitch amulets, I am using the runes as visual and aural representations of the pieces of story that I’m weaving together. This is not so different from how I see and work with materia magica. For me, magic is about story, about bringing smaller stories together to either create or edit a larger metaplot.

Runic Touchstones

There’s also something very powerful about having a symbol or sound to focus on when working magic – especially when you’re working on a piece for a long time. It can give you something to focus on and come back to when your mind wonders. It can also give you something to cling to and put your faith in when scared, And for people who need things to be more concrete than abstract, having those things to hold onto can make all the difference (but more on that in a future post).

Rune Stories, Belief and Change?

But when you get into the realm of story, it’s never as simple as just deciding which stories you connect with and want to tell.

This is a discussion that has been cropping up in response to a post on the origins of the SATOR square. It’s a really interesting post, and in my opinion, very credible. But it has brought up the question of which “stories” are more useful when it comes to the SATOR square? Is the theorized origins story more useful than the ones that came later or are all the stories useful? Can they be selectively tapped into depending on the desired results?

Whatever the answer, the questions are not all that dissimilar from those we need to consider when contemplating modern rune magic. Because despite my desire to distance myself from the influence of Marby and Kummer, the stories they developed are still out there. At this point, generations of runesters have come up practicing modern rune magic, each learning that the runes represent and can be used to tap into cosmic energies.

Now just think about that for a moment.

How much belief, intensity, ritual, passion, and even blood has gone into that?

The runes may not have originally been cosmic energy fields, but after decades of people working with them as though they are (plus the reinforcement from the fantasy genre), can we really say that the runes absolutely do not function in a like manner?

I don’t think we can.

That “story” is part of the wider magical “playing field” we all work on. Moreover, there are plenty of people out there (myself included) who can attest to the efficacy of that approach.

And that isn’t even taking into account other newer stories that are springing up about the runes. For example, you also have people who consider the runes to be beings in and of themselves. I personally cannot agree with that yet, and this is clearly my personal gnosis. But that’s not to say that they won’t ever become beings of a sort, especially if people continue to see them as beings and work with them in that way. I mean, if writers can create characters and then have sightings of them while out and about in the world (as in the case of John Constantine), who’s to say that someday we won’t be hearing of people reporting sightings of a being called FEHU?

Rune Contemplation

One of the things I love to do, regardless of whether a system of magic is ancient or modern, is to create and perform experiments. Modern rune magic is no exception to this and I will be talking about both my experiments and some of the ways that I work over the course of the next couple of posts. In this final section though, I’m going to talk about a couple of contemplative practices I experiment with that involve the runes. Feel free to try them out and let me know how they feel for you!

Where Do You Feel The Sounds?

As I’ve said before, I don’t consider the sounds of the runes to be particularly magical in and of themselves. But I also can’t deny that people have been intoning the runes since the beginning of the modern Heathen revival. Moreover, as “silly” as intoning letters that people use to write every day things may sound to more reconstructionist Heathens, it isn’t unheard of in Indo-European cultures. Pythagoras, for example, considered those everyday ordinary vowels to be the sounds of the planets, and vowel intonation was a part of the Graeco-Egyptian magic of the Greek Magical Papyri. And while I’m making this point, it’s probably also a good time to bring up the Greek Alphabet Oracle. Because for as much as people like to mock others for using letters that some guy called Halfdan might have used to write about his penis size, the Greeks had no problem with using their letters for writing about dick size or as an oracle.

Really, there’s a whole conversation we could have here about how this idea of having a separate language or alphabet for sacred things just doesn’t work when you look at the ancient world, but that’s not why I’m here.

So where was I?

One of the practices I like to do is to intone runes, try to feel where they resonate the strongest in my body, and then contemplate how that location may or may not reflect the stories associated with that rune. So for example, when I intone URUZ, I feel it in my shoulders down to my fists. There’s a battering ram feeling there. But there’s also a feeling of groundedness and standing one’s ground, of being too big to be moveable unless I choose. In turn, I’ve found that this sensation itself brings up certain feelings surrounding being immovable and able to smash things.

When I look to my stories about URUZ – the ones I’ve internalized – I find that the sensations I experience when intoning this rune largely match. It’s the aurochs rune in the Old English rune poem – a beast that can fight and be quite destructive. It’s a beast of mettle, savage. It’s a beast that I imagine can stand its ground.

I’ve found this to be a useful exercise for a couple of reasons. The first is that it gives me insight into the stories I’ve internalized for each rune. The second is that over time, it’s proven to be a way to provoke necessary emotions for the magical work I’m doing. The more I do it and contemplate the sound, the stories, and the emotions, the easier it is to summon those emotions using the sound of the rune itself. This isn’t so different from using self-hypnosis to “program” yourself with body cues for things like grounding.

Grounding and Connecting with the Around World

Speaking of grounding, the second contemplative activity I’m going to describe today focuses on that very thing.

This is something I came up with while walking my dog in the local woods. I begin by closing my eyes and breathing for a moment. Just connecting my breath with the air around me and working to feel that sense of interconnectedness with every being else that breathes. Then, I move into

hard and fast in the earth, supported by its roots,

a guardian of flame and a joy on native land.”

OE Rune Poem

intoning a rune that’s grounding. For some people this is URUZ, for me it’s EIHWAZ (or a combination of the two). As I chant, I let my voice find its own pitch and melody if one comes. I try to feel the vibrations in my body and visualize rooting down deep into the earth.

Then, when I feel like I have got that, then I change to chanting MANNAZ. For me, MANNAZ is the story of connection between not just humans, but all kinds of people. And this is what I focus on as I chant. I focus on that animistic sense of interconnectedness. As strange as it may sound, I strive to allow the boundaries between myself and the rest of the world to melt away until all I can feel is vibration and energy.

And if I’m lucky and actually get to that place (which is surprisingly hard), I tend to set off all the local birds. Which is really neat.

One of my favorite times working with this technique was in a forest with a friend. We’d been walking and I started to show her what I’d been experimenting with. She joined in and we were getting good responses from the world around us. Then she decided to throw in some LAGUZ – the water rune – and it started to rain.

It was brilliant.

Be well, everyone. And happy chanting!

woman on another table called me over to her. She’d decided I needed to have a rune reading from her, and I, several pints into the evening, decided to go along with it.

woman on another table called me over to her. She’d decided I needed to have a rune reading from her, and I, several pints into the evening, decided to go along with it.

around forty-five years now, in a religious movement that’s not really been around for a whole lot longer. In many ways, the origins story of modern rune magic parallels that of Heathenry itself in that many of the early founders of modern Heathenry were also folkish/völkisch. (Btw I really recommend you pick up

around forty-five years now, in a religious movement that’s not really been around for a whole lot longer. In many ways, the origins story of modern rune magic parallels that of Heathenry itself in that many of the early founders of modern Heathenry were also folkish/völkisch. (Btw I really recommend you pick up